Snowy Owl

Bubo scandiacus

Name

The genus name Bubo comes from Latin for “a horned owl,” or “owl of ill omen.” Scandia most commonly refers to the geographical region of Scandinavia.

General Description

Snowy owls, true to their name, blend in well with their Arctic surroundings. They have mostly white plumage, yellow eyes, black talons with white feathers that extend down the leg, and barely noticeable ear tufts. Males and females are sexually dimorphic, although there is a notable overlap in plumage that can make verification in the field difficult. On average females have heavier mottling on the body, giving an overall darker appearance. Juveniles typically have stronger markings than adults, regardless of gender.

Similar Species: Generally an unmistakable species. Snowies are sometimes confused with barn owls in flight, and subarctic great-horned owls which appear lighter than their southern cousins. However, red-tailed hawks account for most misidentifications of snowies, due to their overall light impression when perched with feathers fluffed out.

Fun Facts

• The whisker-like feathers that form the face ruff on snowy owls are denser and more pronounced than on other owls; this allows them to trap and warm air around their face when they breath.

• The snowy owl has been described as “perhaps the most completely nomadic bird in the world.” - Scott Weidensaul.

• Although known as a small-mammal specialist, snowy owls will occasionally feed on whale carcasses in the Arctic, and dolphin carcasses on the Atlantic coast.

• Great-horned owls and snowy owls are, in some ways, geographical counterparts; where the great-horned owl’s range ends, the snowy owl’s begins, they are of comparable size & shape, and they have a similar impact on the food web in their respective zones.

• Snowy owls can endure temperatures below -68°C (-90°F).

• Individuals sometimes use sea ice during winter and can be seen up to 210 km from land in search of vulnerable waterfowl congregating in open leads of water called polynyas.

Size

| Females | Males | |

| Wingspan | 1.5 m (~4'11") ✏️✏️✏️✏️✏️ ✏️✏️✏️ 8 pencils end to end | 1.4 m (~4'7") ✏️✏️✏️✏️✏️ ✏️✏️ 7 pencils end to end |

| Mass | 2.1 kg (4.6 lbs) 🍈🍈 1-2 melons | 1.6 kg (3.5 lbs) 🍈 1 melon |

Vocals

Most snowy owl vocals occur during the breeding season. Males (and occasionally females) emit a loud, hoarse hoot that can be heard up to 2 kilometers away, mostly as a territorial call, a “threat hoot” towards intruders, or occasionally as a male approaches and departs his mate. When giving a territorial hoot, males tip forward and raise their tail. During nest defense, both sexes are known to give a barking “kre” call. Males will use short hoots to warn the entire family of the presence of intruders, or alert them to a food deliver. Females make a unique high-pitched call when feeding and after copulation. Like other owls, snowies will snap their bill and hiss when threatened.

Habitat

Snowy owls breed in the tundra and prefer shrub-free, high locations for their nest sites. Snowy owls breeding in North America usually choose rolling hills in coastal plains typical of the North American Arctic Archipelago, such as Bylot Island, but they have also been recorded nesting on glacier moraine and around wet polygon meadows. During the winter, some individuals move south and temporarily reside in open habitats such as grasslands, farm fields, airports, and other minimally treed landscapes that provide optimal visibility for hunting. Others stay north, subsisting off of waterfowl and other opportunistic prey resources such as ptarmigans and/or arctic hares.

Feeding

Snowy owls are rodent specialists, feeding almost exclusively on collared and brown lemmings during the breeding season. The “boom and bust” population fluctuations of these nutritious rodents have widespread effects on the Arctic food web. Because there are fewer species interactions in the Arctic compared to regions with a more consistent growing season and increased productivity (such as the Tropics), lemmings are an especially key species within the integrity of the Arctic ecosystem. They are a staple prey item for not only snowy owls, but Arctic foxes, weasels, ermines, rough-legged hawks, and pomarine, parasitic, and long-tailed jaegers. In years of very high lemming abundance, snowy owl nests can literally be lined with lemmings, which the female and the nestlings will eventually consume.

Although snowy owls are lemming specialists, they have proven adaptable especially outside of the breeding season when the accessibility or availability of lemmings is too low to compose the entirety of their diet. In these circumstances, the owls supplement their diet with other prey, or move to alternative locations. The size and shape of their feet allows them to take a variety of prey such as herons, ducks, gulls, geese, and the even the occasional muskrat or pigeon. An analysis of five thousand snowy owl pellets from Massachusetts revealed the presence of over 30 bird species!

Nesting

In courtship, males usually carry a lemming in their beak while performing a highly visible oscillating flight for their prospective mate. This display is often accompanied by hooting and a ground display.

The nest consists of a mere scrape in the ground, located on top of a hummock or raised parcel of earth. Eggs are typically laid in the last three weeks of May, although exact timing fluctuates with annual variations in snow cover and snowmelt. In years of high lemming production, a female snowy owl may lay anywhere between 2 and 11 eggs, while in low lemming years they usually don’t breed at all. Snowy owls are seemingly adept at scouting for potential nest sites and selecting based on lemming presence. They are a classic nomadic species, demonstrating impressive breeding dispersal from one year to the next. Snowy owls exhibit much lower site fidelity (returning to the same site in consecutive years), than other raptors since the presence of their preferred food, lemmings, is unpredictable from year to year.

Incubation lasts roughly 32 days, and eggs hatch asynchronously. The female incubates while the male delivers prey, and nestlings are fed exclusively by the female. Nestlings experience rapid weight gain in their first month of life, going from 45 grams (1.4 ounces) to 1800 grams (4 pounds) in a few weeks. One study on Baffin Island documented nestlings consuming an average of 2 lemmings per day, and adults an average of 3 to 5.

Migration

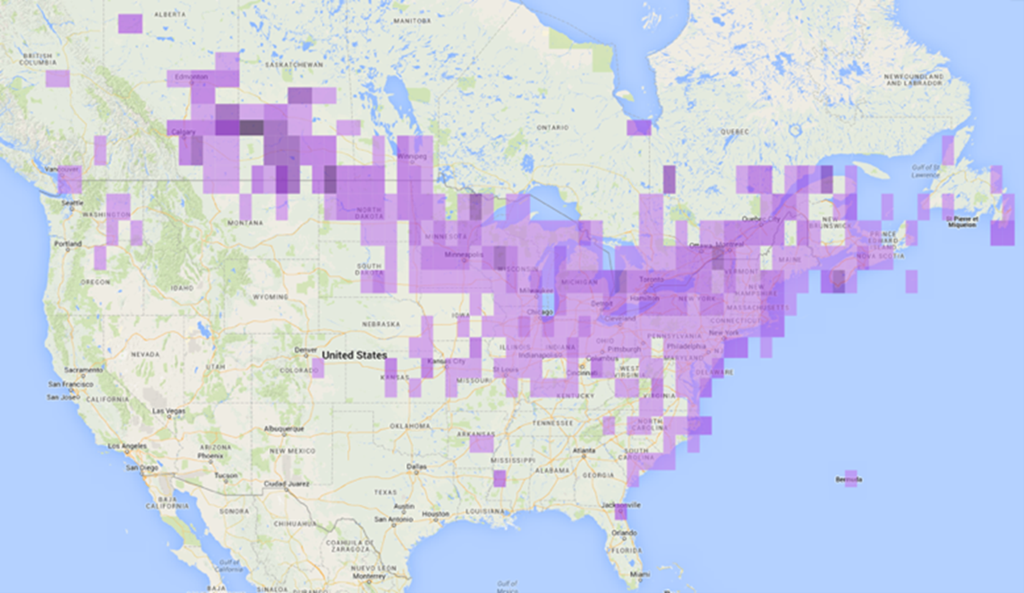

If you’ve had the pleasure of seeing snowy owls in unexpected places within the United States, you have likely witnessed a phenomenon called a winter irruption. This is when higher-than-usual numbers of snowy owls move south, gracing farm fields, mountaintops, airports, and other open habitats with their presence over the winter. The reasons for irruptions are still being understood, but we know that these extreme influxes are a result of high lemming numbers in the Arctic during the preceding summer. With more lemmings available, females lay larger clutches and given the high success rate for snowy owls, many of those hatchlings survive to adulthood. Therefore, the majority of irruptive snowy owls seen in the United States during irruptive years are juveniles in good body condition, likely moving south to avoid competition from adults. The details of juvenile movements are currently being investigated by a dedicated team of researchers including Hawk Mountain’s Senior Scientist Dr. JF Therrien.

One of the largest winter irruptions of snowy owls ever recorded was during the winter of 2013-2014 when an estimated 306 owls were recorded in Newfoundland, 400 in Massachusetts, and 300 in Pennsylvania. For comparison, Pennsylvania usually records 1 or 2 snowy owls per winter.

In 2007, Dr. JF Therrien collaborated with colleagues to investigate the movement ecology of snowy owls tagged on Bylot Island. They discovered that during the winter, some individuals subsist off of waterfowl congregations in open bodies of water within the ice pack called polynyas. This was a groundbreaking discovery. Prior to these movement tracks, biologists assumed most snowy owls moved south during the winter, accounting for some of the sightings of adults in the northern United States during this time of year. It turns out there is much variability between individual movement choices than previously thought.

Current Conservation Status

Given the instability of the Arctic climate, the conservation status of snowy owls is uncertain. Currently snowies are labeled vulnerable on the IUCN’s Redlist (International Union for Conservation of Nature). Increased rainfall, eroding sediment, melting sea ice, and the shifting timing of snowmelt are all consequences of climate change that are impacting the Arctic environment as we speak. As top predators, snowy owls will undoubtedly need to adapt to these and perhaps other environmental changes. Researchers across the snowy owl’s range have coalesced to form the International Snowy Owl Working Group, an organized body of experts who intend to clarify population size, population trends, and inform policies that will protect snowy owls from manageable threats such as electrocution and collisions with cars and planes. In 2010, this group stated that “climate change has a significant impact on the onset of spring and snowmelt in the breeding areas which may change the availability of prey for the species.” That was a decade ago.

How can you help snowy owls?

Many of us may never visit the Arctic. Naturally, without witnessing this changing landscape firsthand, it is difficult to relate to the challenges faced by Arctic species. Therefore, one of the things we can do for snowy owls is to bridge this information gap by keeping ourselves informed and having conversations with our peers, colleagues, friends and families about climate change, and the consequential impacts on Arctic ecosystem health. In other words, we can help snowy owls by paying more attention. By staying up to date with the changes occurring in the Arctic, we are prepared to discuss issues affecting the region, and we are prepared to take action when the opportunities arise. Click here for a blog describing 5 reasons to care about the Arctic.

If you want to do more for snowy owls, the World Economic Forum emphasizes the importance of demanding action “from yourself, your city, your country, and from the companies that make all the goods and services you consume.” They suggest the following:

- Demand action from yourself by reducing your own emissions when possible (see 20 ideas on how to do this at globalstewards.org).

- Support companies and politicians who are leading change that will help the Arctic.

Another way you can help snowy owls is by funding research that sheds light on how the changing climate will affect ecosystem integrity in the Arctic. To support research on snowy owls, contact Senior Scientist Dr. JF Therrien at [email protected].

Special thanks to Dr. JF Therrien, Audrey Robillard, and Traci Sepkovic for their generous photo contributions to this account.

Information written and compiled by Zoey Greenberg.

Sources

Global Stewards (2020). Top 20 ways to reduce your carbon footprint. Retrieved from

http://www.globalstewards.org/reduce-carbon-footprint.htm

IUCN. Snowy Owl. Retrieved from

https://www.iucnredlist.org/species/22689055/127837214#conservation-actions

Johnsgard, P. A. (1988). North American owls: biology and natural history. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press.

Project Snowstorm. What is an irruption? Retrieved from

https://www.projectsnowstorm.org/what-is-an-irruption/

Rolf A. Ims, Eva Fuglei, Trophic Interaction Cycles in Tundra Ecosystems and the Impact of Climate Change, BioScience, Volume 55, Issue 4, April 2005, Pages 311–322, https://doi.org/10.1641/0006-3568(2005)0552.0.CO;2

Therrien, J., Gauthier, G., & Bêty, J. (2011). An avian terrestrial predator of the Arctic relies on the marine ecosystem during winter. Journal of Avian Biology, 42(4), 363-369. Retrieved January 15, 2020, from www.jstor.org/stable/23018134

Weidensaul, Scott. (2015). Owls of North America and the Carribean. New York: NY.: Peterson Field Guides.

Whiteman, Gail & Wilkinson, Jeremy. (02015 September 03). 3 ways you can save the Arctic ice. Retrieved from

https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2015/09/3-ways-to-save-the-arctic-ice/