Ospreys are cosmopolitan raptors.

Pandion haliaetus

67-year annual average: 374

1992-2001: 575

Record year: 872 (1990)

Best chance to see: Mid- to late September.

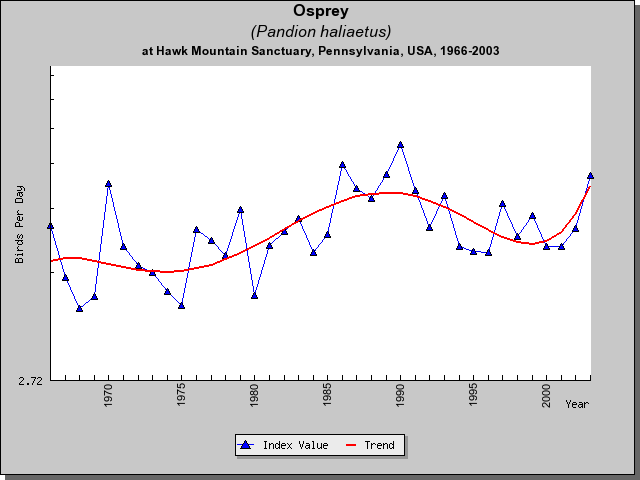

Longterm trends: Increasing from 1930s through 1990s, possibly in response to increasing numbers of reservoirs and beaver ponds in North America. Reintroduced in many areas including Pennsylvania in the 1980s.

A.K.A. Fish Hawk, Fishing Eagle

Field marks: Large, eagle-sized, fish-eating raptor, with long, narrow, crooked-wings, and long legs. Generally white below and dark above, with a white head, dark eye-stripe, and dark, banded tail.

Flight behavior: Typically migrates alone, sometimes in flocks of 2-4 birds. Osprey wings are sharply angled at the wrist, resulting in an “M” shaped silhouette like that of a gull. Often migrates late in the afternoon.

What Size is a Osprey?

- Wingspan6'-6'6"

- Length1'9"-2'2"

- W-L ratio2.7:1

- Weight2.5-4 lbs

Raptor Bites

- Ospreys are the only member of the family Pandionidae.

- Were once known as “fish hawks” because they usually eat fish.

- Have “M” shaped leading edges to their wings that make them appear gullwinged.

- Ospreys add material to their nests each year, and sometimes build massive structures weighing up to 400 pounds.

- Fish by hovering for several seconds before plunging--talons first and wings tucked-- into water.

- Have reversible outer toes and spiny foot pads that help them catch and hold fish.

- Carry fish head first to make them more aerodynamic in flight.

- Most fish caught by Ospreys weigh about half a pound.

- Osprey are sometimes drowned by fish too large for them to carry.

- Populations of Ospreys declined drastically in the middle of this century because of the misuse of DDT and other pesticides.

- Get their scientific name from Pandion, a mythical king of Athens and haliaetus, which is Greek for sea eagle.

- Are a cosmopolitan species with populations on all continents except Antarctica.

Seasonal Count – from North Lookout – 1934 to Date

Introduction

The Osprey is a cosmopolitan raptor that breeds or migrates on all continents except Antarctica, as well as on many oceanic islands. Ospreys occur in a range of habitats, but always near water. This species feeds almost exclusively on live fish, which are usually taken in shallow water. Ospreys have oily, somewhat water-repellant feathers, and long, unfeathered legs to help them stay dry as well as flexible outer toes, and small, spiky scales covering the soles of their feet to help them hang on to their prey. Because they feed on fish, Ospreys sometimes are viewed as a threat by fishermen and aquaculturalists. In North America, the widespread use of DDT caused Osprey numbers to decline precipitously during the 1950s, 1960s, and 1970s. Following the ban on the widespread use of this pesticide in 1972, many populations of Ospreys recovered. Today, Ospreys continue to increase in number. Osprey Identification Ospreys are large, eagle-sized raptors. The species has long, thin, gull-like wings and flaps with stiff and deliberate wingbeats. In flight, Ospreys hold their wings in a “crooked” position that gives the species a distinctive “M”-shaped profile. The Osprey has a mostly white head with a thick dark-brown eye stripe that continues down its neck and onto its back. Adults have yellow eyes, dark chocolate brown upper parts and mostly white breasts and bellies. Juveniles largely resemble adults except that their eyes are orange-red and their brown contour feathers have cream-colored edges. Female Ospreys typically are larger than males and often have more dark speckling on their breasts.

Breeding Habits

Ospreys are usually monogamous and rarely polygamous. Pairs repeatedly return to the same nest site, and often remain together for many years, sometimes, for life. Older individuals and, in particular, pairs that have bred together previously, tend to be more successful than newly formed pairs. Most Ospreys do not return to their breeding grounds until the spring of their second year, and a few remain on their wintering grounds until the spring of their third year. Ospreys typically breed for the first time when they are three or four years of age. Males return to the breeding grounds before females and select the nest site. Some males perform aerial displays even before females arrive. The displays, which peak after the female arrives, allow the male to “mark” his territory and to solicit the attention of a female. So called “sky dances” usually begin and end at the nest site, and while performing the display, males usually carry a fish or nesting material and call repeatedly. “Sky dances” incorporate undulating flights, which sometimes reach heights of 300 feet or more. At the top of each undulation, males typically hover briefly with their legs dangling and their tails fanned, and then dive downward with their wings drawn in. They may repeat this sequence several times. During courtship, males also provide food for their mates, follow them closely, and chase away other males. Ospreys prefer to build their large stick nests near water at sites with good visibility and limited access for predators. Typical nest sites include dead or relatively open live trees in or within a few kilometers of open water. Cliffs, rocky outcrops, and even cacti are sometimes used. On rare occasions, Ospreys nest on the ground. They also nest on utility poles, duck blinds, channel markers, and nesting platforms erected specifically for them. Nests usually are renovated and reused annually either until the base collapses or until the nest is damaged in a storm. Nests often are five feet across and two to three feet deep when they are first built and increase in size each year thereafter. Smaller birds, including House Sparrows and Monk Parakeets, sometimes nest within an Osprey’s nest. Osprey pairs can construct their nests in as few as seven to 10 days. Males gather most of the material for the main structure and females collect most of the material for the nest lining. Although pairs defend the immediate area around the nest, Ospreys sometimes nest in loose colonies in areas where prey is abundant. Ospreys typically lay two or three egg clutches. Incubation begins when the first egg is laid and clutches hatch asynchronously. When food is limiting, younger chicks that are unable to compete with their larger, older siblings often starve. Females do most of the incubating during the 34 to 40 day incubation period. After the eggs hatch, the female broods the nestlings continually for ten days. Throughout this period, the male provides food for the female. Nestlings are able to feed themselves when they are about six weeks old, at which time females begin to hunt for themselves and their young. The young leave the nest when they are seven to eight weeks old, and will continue to roost at and around the nest for another month. During the day, fledglings perch near the nest and will sometimes fly after the male begging for food while he hunts. Young usually catch their first fish two to eight weeks after fledging.

Feeding Habits

Although there are anecdotal reports of Osprey catching mollusks, snakes, birds, and mammals, fish comprise more than 99% of the species’ diet. Unlike the Bald Eagle, Ospreys usually do not feed on carrion. Most Ospreys are opportunistic and feed on the most accessible, abundant, and appropriately-sized fish available. The species is not designed for deep diving and most fish are caught at or near the surface. Ospreys usually search for their prey from the air. Doing so is more energetically costly than perch-hunting, but it enables Ospreys to search for food across greater areas. Perch-hunting is more common in winter when individuals only need to feed themselves. While hunting, Ospreys fly slowly over the water and often hover briefly when scanning intently. When an Osprey detects a fish, it tucks its wings and drops toward the water. While descending, the Osprey uses its wings and tail to adjust its position. Ospreys plunge into the water feet-first with their legs and talons fully extended. After diving, Ospreys rest for a moment on the water and secure their grip on their prey before taking off. Once airborne with a fish, Ospreys place one foot in front of the other, and rearrange the fish so the head faces forward. The Osprey’s flexible outer toe allows it to carry fish with two talons securely placed on either side of its prey. Hunting success depends on the age of the Osprey, type of fish, and weather. Young Ospreys are less proficient hunters than adults. Ospreys typically catch slowmoving, bottom-dwelling species and are least adept at capturing fast-moving fish. Hunting becomes more difficult in choppy and murky water. The presence of emergent and submerged vegetation also decreases hunting success.

Migration

The Osprey is one of five North American raptors that are complete migrants. The Osprey’s diet of live fish makes migration from many high-latitude areas a necessity. Fish become unavailable not only when water freezes over but also when cold temperatures cause fish to migrate to deeper waters. As a result, across its range, the Osprey is sedentary at low latitudes and completely migratory at high latitudes. In North America, most populations migrate long distances, but in much of Florida, Mexico, and the Caribbean Ospreys are sedentary. Migrants avoid wintering in areas where non-migrants breed and they exhibit fidelity to specific wintering areas and migration routes. The species is believed to follow the same routes both in autumn and spring. Ospreys are broad-frontal migrants at high latitudes, but tend to follow leading lines farther south. Unlike many raptors, Ospreys do not depend on soaring on updrafts and thermals to complete their migratory journeys. The species is willing to cross large bodies of water and other areas of inhospitable habitat like deserts. Ospreys will fly early and late in the day when thermals are either weak or non-existent. Eastern breeders generally winter in South America and in the Caribbean. On their southbound migrations, Ospreys from eastern North America tend to fly between the Atlantic Coast and the Appalachian Mountains and cross the Caribbean Sea to South America. Western breeders generally migrate south across the western United States along a broad front. Most western Ospreys overwinter in Mexico or Central America. Overall, the migration routes of eastern and western Ospreys tend not to overlap, and Ospreys from eastern North America migrate further south than Ospreys from western North America. Breeders from the Midwest overlap with both eastern and western birds both on migration and on the wintering grounds. Differences occur not only among regions, but also among individuals within the same regions. In autumn, females usually migrate before and typically winter further south than males. In many instances, females leave before the young are independent, and the male continues to provide food for the young after the female’s departure. Adults typically migrate before juveniles, and most juveniles remain on their wintering grounds at least until their second spring. At high latitudes Ospreys migrate alone or in small groups. Farther south, larger flocks of up to 50 or more birds have been observed. Large flocks in Cuba have been attributed to the Osprey’s tendency to concentrate at the tips of islands and peninsulas in an effort to shorten water crossings. Like many other raptors, Ospreys do not deposit large amounts of fat prior to migration. Because they tend to expend a lot of energy on migration, they often refuel en route at places where prey is abundant and available. Ospreys are sometimes seen carrying fish with them while migrating, something that is rarely observed in other migrating raptors. At Hawk Mountain, Osprey migration peaks in late September. The longterm (1934- 2002) average autumn count for Hawk Mountain is 380 Ospreys. The average count for the past 10 years (1993-2002) is 580.

Conservation Status

The current world population of Ospreys is thought to be fewer than 100,000 birds. In 2001, the number of breeding pairs in the lower 48 United States was estimated at between 16,000 and 19,000. In the 1950s, and 1960s, Osprey populations decreased and the species was extirpated from many areas due to the effects of organochlorine pesticides like DDT. When Ospreys consume fish containing pesticides such as DDT, these chemicals accumulate in an Osprey’s fatty tissues. DDT and other organochlorine pesticides compromise reproductive success by causing eggshell thinning. Osprey populations have increased in the United States since the late 1970s. Numbers increased primarily due to a ban on the widespread use of DDT in 1972. Today, Osprey numbers in the United States are increasing and individuals are returning to formerly vacated breeding grounds, as well as expanding into new areas. Restoration efforts involving reintroduction programs, as well as the provision of artificial nest sites, aided in the Osprey’s recovery. Artificial nest platforms provide increased numbers of available nest sites and offer sturdy, safe nesting locations. Today, many Osprey populations nest almost entirely on artificial nest sites. Ospreys continue to be shot in some parts of their range, particularly at fish farms in Latin America and South America. Although Ospreys tolerate human activity, excessive disturbance can disrupt nesting. Collisions with vehicles and powerlines also are sources of mortalities. Electrocution is another threat to Ospreys around powerlines. Environmental contaminants continue to be a potential source of fatalities as well.

| BWHA Trends | ||

| Year Range | Trend Value | P |

| 1970-1980 | 1.3 | .25 |

| 1974-2004 | 1.5 | 0 |

| 1980-1990 | 3.1 | 0 |

Osprey Reading List

DUNNE, P., D. SIBLEY, AND C. SUTTON. 1988. Hawks in flight. Houghton Mifflin Company, Boston, Massachusetts.

FERGUSON-LEES, J. AND D.A. CHRISTIE. 2001. Raptors of the World. Houghton Mifflin Company, Boston, Massachusetts.

JOHNSGARD, P.A. 1990. Hawks, eagles, and falcons of North America. Smithsonian Institution Press, Washington, D.C.

MARTELL, M.S., C.J. HENNY, P.E. NYE, AND M.J. SOLENSKY. 2001. Fall migration routes, timing, and wintering sites of North American Ospreys as determined by satellite telemetry. Condor 103: 715-724.

POOLE, A.F., R.O. BIERREGAARD, AND M.S. MARTELL. 2002. Osprey (Pandion haliaetus). No. 683 in The Birds of North America (A. Poole and F. Gill, Eds). The Birds of North America, Inc., Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

POOLE, A.F. 1989. Ospreys: A natural and unnatural. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, U.K.

RODRIGUEZ, F., M. MARTELL, P. NYE, AND K. BILDSTEIN. 2001. Osprey migration through Cuba. Pp. 77-79 in Hawkwatching in the Americas (K. Bildstein and D. Klem, Jr., Eds). Hawk Migration Association of North America, North Wales, Pennsylvania.

SNYDER, N. AND H. SNYDER. 1991. Raptors: North American birds of prey. Voyageur Press, Stillwater, Minnesota.

STOKES D.W. AND L.Q. 1989. A guide to bird behavior, volume III. Little, Brown and Company, Boston, Massachusetts.

WEIDENSAUL, S. 1989. North American birds of prey. Gallery Books, New York, New York.

WHEELER, B.K. AND CLARK, W.S. 1999. A photographic guide to North American raptors. Academic Press, San Diego, California.