Life of a Scavenger

Posted on January 07, 2021 in Science

One of the most interesting aspects of a bird is their migration pattern. Some species travel great distances for food, warmer weather, and mating, causing them to exert a significant amount of energy and make multiple stops along the way to their final destination.

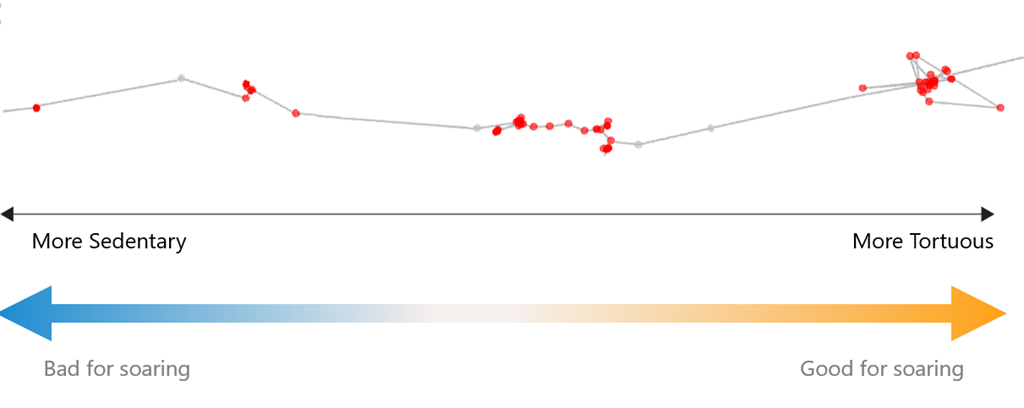

Non-migratory birds are seen as residential members of their environment, while obligate migration is an extremely rare wildlife behavior, present in geese for example. The birds will choose to either shorten the time they spend flying or they will minimize the energy used during resting periods. Their flying consumes energy, and the more energy they take, the more they will need to rest. Soaring birds like vultures aren’t held back by these energetic limitations due to their larger body mass and the ability to use passive flight. They fly at a low cost by using thermals but can only move during certain weather conditions. Poor conditions can leave them on the ground, unable to fly.

Out of the several vulture species, turkey vultures are one of the two migratory vultures that the Sanctuary sees. Worldwide, turkey vultures are the most widespread, in part because they do not require a specific habitat. They fly with their wings held at an angle, called a dihedral, which allows them to soar without flapping their wings. Turkey vultures are scavengers, and because of how difficult it can be to find a carcass, they can frequently go days without any food. Additionally, they use very little energy during their activities. This is shown especially in their minimum number of stops, which Dr. Mallon estimates is as long as 23 days without feeding.

In the study of the three populations, she discovered that there were two types of stopovers, which were either a few hours or several days. Seasonal effects were also seen in the differing populations, because in the fall there were significantly more stopovers than there was in the summer. For example, one individual completed its fall migration in 45 days but took only 33 days to complete its spring migration and therefore required less fat. This was possibly due to most birds looking to get to their breeding grounds as quickly as possible in the spring. Along migratory routes there is strong competition from other raptors, which gives the assumption that there is a lack of food during migration.

Dr. Mallon conducted this research at the University of Maryland, College Park and was advised by Dr. Bill Fagan.

Turkey Vultures are the most common species of vulture in the United States. Their migratory patterns show how efficiently they can use their energy to ensure that they reach their destination. They are also a model species for studying soaring flight—meaning they are well-adapted to soar—and by studying their flight behavior, we can apply what we learn to other species that are more challenging to study.