Black harrier research: west to east migration?

Posted on February 25, 2019 in Science

Dr. Marie-Sophie Garcia-Heras, a former leadership trainee during autumn 2017, recently published a paper on the migratory patterns and settlement areas of the black harrier, Circus maurus. This medium-sized bird of prey is endemic to Southern Africa, meaning they exist only in that part of the world. Black harriers are endangered in Southern Africa, with a population size estimated at less than 500 breeding pairs. They are small-mammal specialists feeding mostly on striped mice (Rhabdomys pumilio), but they also prey on birds and lizards. Black harriers nest exclusively on the ground in areas with natural vegetation along the south-western South African coast. A decline of the population has been suspected in the last four decades, mainly due to the destruction and fragmentation of their natural habitats.

World-wide, the majority of bird migration studies have focused on intercontinental migrants, meaning birds that cross continental boundaries. Too often, these studies focus solely on long-distance migrants, who migrate North to South, while relatively little is known about medium or short-distance migrants. Furthermore, in recent decades Africa has seen a decline in many raptor species due to habitat fragmentation, persecution, and exposure to poisons and contaminants. Therefore, studying raptors that migrate within the borders of the continent (referred to as Intra-African migrants) has reached a heightened relevancy.

Within this context, the primary goals of Sophie’s study were to 1) describe for the first time the overall migration patterns of the Black Harrier and 2) identify areas used in both the breeding and non-breeding seasons.

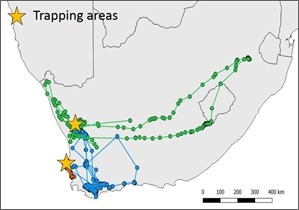

From 2008-2015, Sophie and Dr. Rob Simmons, her former PhD supervisor, deployed tracking devices on 13 breeding adults; nine females and four males. The devices were programmed to send one location every hour. Patterns from the data showed that black harriers exhibit great individual variety in their movements: 70% migrated up to 1400 km away from their breeding areas, completing a unique West to East migration, while other tagged individuals engaged in medium distance (100-400 km), or short-distance migrations (less than 100 km).

Essentially, when it comes to black harriers, individuals migrate to the beat of their own drum.

Based on what we know about the black harrier’s feeding ecology, it is reasonable to suggest that these horizontal migrations could be in response to movements of their primary prey. Indeed, Black Harriers are speculated to “follow the food,” which is characteristic of predators that specialize in rodents due to their sometimes roller coaster-like population dynamics and/or responses to environmental patterns (rainfall). The birds in Sophie’s study that showed an Eastward migration did so as the South-Western part of South Africa entered into its dry season, and the Eastern part of the country into the rainy season.

Another interesting finding was that the harriers flew twice as fast during post-breeding migration than during pre-breeding migration, while most migrants do the opposite. One possible explanation for this could be that Black Harriers spend time “prospecting” before choosing a breeding site presumably to search for the best combination of vegetative cover (to lessen the chance that their ground-dwelling chicks will be preyed upon) and adequate prey availability and abundance. Therefore, some adults have been traveling hundreds of kilometers away from their former breeding ground in hopes of finding the best habitat for a new breeding ground.

Overall, eight black harriers ceased transmitting during the non-breeding season or during a migration event. In four cases, the deaths could be confirmed: 1 car collision, 1 apparent poisoning, and 2 collisions with power lines. These losses further support one of the primary themes of emerging raptor movement ecology studies: the more we learn about year-round movements and habitat preferences of a species, the more successfully we can inform management decisions that lessen risk of mortality, and proactively secure a future for the birds at stake. For black harriers, these studies can increase protection of critical areas, allow energy companies to create risk maps prior to erecting wind turbines, and identify areas with survivorship threats such as contaminants.

Thanks to Sophie’s hard work, we have a deepening understanding of Black Harriers and an inspiring example of how thoughtfully achieved movement ecology studies are a valuable tool for the raptor conservation community at large. We would like to commend Sophie for her contributions to raptor conservation, and emphasize our pride in hosting her at the mountain during the writing process for this publication. We hope to see her back soon!