The Great Challenge of Diversity and Inclusion in Global Conservation

Posted on in In the Field by Ernesto Ruelas Inzunza, Hawk Mountain Board Member

Sean Grace, Hawk Mountain’s President, wrote me a few days ago to commend me and a large group of Latin American and Caribbean ornithologists who recently published two articles in Ornithological Applications, the world’s leading ornithology journals (see references below). Our articles discuss multiple barriers that ornithologists from the Global South (Latin America and the Caribbean, Africa, and Southeast Asia, among other regions) face in the practice of our science. We raised issues such as facing northern-biased views of novelty and scientific research worth, parachute science, English language hegemony, and a lack of openness to multiple perspectives.

Sean sent me a quote from an article in Science, one of the world’s top scientific journals, that discusses our papers: “(One paper denounces) …few Latin American ornithologists in leadership roles, and a bias against citing papers in Spanish and Portuguese—that they say have often marginalized the region’s researchers. In the other (paper), a smaller group offers 14 recommendations for how the field’s major journals can revise their policies and practices to improve the flow of science from the region’s bird scientists.”

A Conservation Center

I gave my first-ever scientific conference presentation in October of 1989 in Veracruz City, Mexico, a place two hours away from home. I was a junior in college at the Universidad Veracruzana, and the conference was the Raptor Research Foundation’s annual meeting. My presentation was a descriptive account of raptor migration along the Gulf of Mexico coastal plain. I met a lot of people there—mostly academics, and some people involved in raptor conservation. In the audience was Dr. Jim Bednarz, the Hawk Mountain director of science at the time. Jim handed me a brochure describing the Hawk Mountain internship program and an application form, and enthusiastically encouraged me to apply. I thought I would give it a try but thought that being accepted was a long shot.

I did and it worked! My application was accepted. Once I made it to Hawk Mountain, I learned that Dr. Bednarz had left for a position as a professor in Arkansas, so I instead got to work under Dr. Laurie Goodrich’s supervision. My project was an investigation on red-tailed hawk migration and how these hawks follow the Kittatinny Ridge (or not) as a leading line depending on wind speed and direction. Working with Laurie was an amazing experience, and so was working on many other things at Hawk Mountain, from education programs to sanctuary maintenance. There, I learned of the intimate connection between science and conservation and stopped thinking of the two as separate fields. I met many great people, and some of them are still my friends.

When I started my relationship with Hawk Mountain, I had some idea about what my internship was going to be like, but the truth is that I wasn’t really that prepared to face one of the most transformative experiences in my life. (Well, I was very young and impressionable at the time, but if I look back to all the things that I have done and the places that I have seen, it is still, professionally speaking, one of the best things that has ever happened to me.)

The Hawk Mountain that I experienced wasn’t a research institution as I originally thought. It wasn’t an education facility or a graduate program or a private preserve either. I could define it for myself as a place that intertwines science, education, and land stewardship—a conservation center. During my internship (now called traineeships), I had a chance to meet an intern from Germany and three others from the United States. Upon reading back issues of Hawk Mountain News, I discovered that people from many other countries had been there: Europeans, Africans, Middle-Easterners, Asians, and a few other Latinos.

I learned a lot during my fall internship and felt deeply motivated by all the wonderful things I experienced. While I was an intern, I worked with Laurie and Jim Brett, Hawk Mountain’s curator, to develop a more systematic investigation of raptor migration in Mexico and started the Veracruz River of Raptors Project (VRR), a long-term monitoring and conservation initiative whose story deserves a separate blog post.

The Difficulty of Exporting Models

Coming back to Mexico after my internship and launching the VRR had its difficulties. Some of them were obvious to me and mostly money-related, such as securing equipment, a vehicle for field work, and administrative support from an established entity that could handle our finances. Other difficulties were of a different type, for example, related to language or culture: most of the materials that I had brought with me, such as books, paper reprints, and training materials for my field crew, were written in English. Some of the education materials that worked very well for Hawk Mountain were culturally inappropriate for Mexico (not that they were wrong or misleading, but they were developed for temperate zone habitats, birds, education backgrounds, and conservation problems of the north).

After our first field season, it became apparent that we needed to find a conservation non-profit to provide us with institutional support for fundraising purposes and to operate the administration side of our project. I tried one of the local research institutions and the university, but they were uninterested and paying for their services was a price that was much too high for our fledging initiative. Beginning our own organization was certainly an option, and an interesting opportunity arose when I learned that Pronatura, a Mexican non-profit conservation organization very similar in structure and operations to The Nature Conservancy of the United States, was opening an office in Veracruz and looking for a director.

During my internship, I had seen Hawk Mountain’s organizational structure and was familiar with a non-profit governed by a volunteer board of directors and run by professional staff. With this background, I thought I could take the director position at Pronatura Veracruz, and I could introduce the VRR as one of their programs and run things the way Hawk Mountain does in Pennsylvania.

Just as importing training and education programs had been a challenge, following the northern model was something that required, at the very least, significant adjustment efforts. Running a conservation non-profit in Veracruz required a better-planned organizational structure that would work under Mexico’s legal, political, and operational circumstances.

Conservation non-profits in the United States are commonly governed by a mix of philanthropists and entrepreneurs that also act as donors to some of the organizational causes, regularly opening doors to other financial resources and providing guidance to many of their operations. “Give, get, or go,” I was once told was the job of a board member.

Businesspeople, lawyers, policy makers, community leaders, renowned scientists, and people with other high-level profiles are frequent members of North American conservation non-profit boards. That doesn’t work well in Mexico, whose philanthropic culture is in diapers. Non-profits struggle with crushing overregulation, nightmarish legal framework for tax deductions (which are non-functional in practice), and the lack of people looking for places to volunteer their talents (even less so people with the profiles required of a board member).

That meant the textbook-type recommendations for running a conservation project and a non-profit organization failed in little or big ways. Many of these failures came from importing and using (with no questions asked, objections raised, or adjustments made) tactics or strategies that work well in other places but had a weak footing on local realities.

Global Raptor Conservation - Diversity and Inclusion in Science, and Why It Is Important

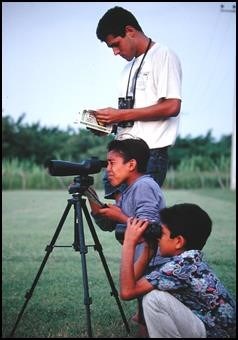

The Hawk Mountain website prominently says, “Global raptor conservation.” When the subject of your efforts is migrating raptors, it makes a lot of sense to be global. Becoming global, however, has been a task of several decades and formidable efforts. And it started, I think, from the bottom-up: Hawk Mountain’s internship/traineeship program started in the 1980s and has since trained nearly 500 young scientists from 75 countries. Many of them have followed careers in conservation, science, education, etc. It is one of Hawk Mountain’s most successful long-term programs!

Looking back to what my Latin American and Caribbean colleagues and I wrote about ornithology, I can see how the present-day system of exclusion came to be. Modern science formally arose in Europe, and scientific, peer-reviewed publishing was invented in the United Kingdom. It is easy to find a direct connection between the present practice of science and its colonial roots and to understand how that carries consequences to this date. In becoming a global endeavor, science and its institutions (including scientific societies) have inadvertently kept some of its old self-absorbed traditions and excluded an important body of knowledge and a growing cadre of scientists vigorously rising in countries of the Global South.

Dr. Diane Husic, a Hawk Mountain board member, chair of the conservation science committee, and a professor at Moravian College that has worked for decades in Costa Rica, pointed out that something similar has happened in conservation. The one-way flow of conceptual approaches, tools, and expertise that has traditionally gone from north to south has incrementally received pushback from the south. The current two-way flux has influenced and strengthened the growth of conservation as a global endeavor, and Hawk Mountain’s trainee program is an example of that. It has taken training and tools for science, education, and conservation devised primarily in North America and adapted them to be effective in other regional and local contexts. Trainees have developed ways to establish migration monitoring sites, designed education and outreach programs, and contributed to raptor conservation as part of their own country or regional agendas, all while closing a feedback loop and improving its original sources. Some of Dr. Husic’s experiences in sustainability and climate change and my own experiences developing conservation initiatives in Mexico followed similar paths and reached analogous conclusions: protected areas and conservation initiatives should no longer simply follow orders designed or written at a desk in a faraway place, but instead be deeply rooted and reliant on the involvement of local and indigenous peoples to cater to regional and local realities. This is where becoming global has also become an issue of diversity and inclusion.

Being diverse and inclusive means more than bringing people of a different skin color or language to the table. It means that the perspectives of these people, and their views of what works and what doesn’t work in conservation (or in science), shouldn’t only “be heard,” but be part of the core principles for effective, global conservation. Ensuring a diversity of voices in conservation leadership is important because the cross-pollination of ideas enriches views and provides solid foundations.

In following this logic—and as an outcome of Hawk Mountain’s most recent strategic plan (June 2020)—the board of directors decided to diversify its membership and invite different voices to join this leading group. Ana Castaño (from Colombia) and I have brought our Latin American perspectives of migratory raptor conservation to Hawk Mountain’s governance. The process itself has been deeply fulfilling, with plenty of dialog and mutual learning. There is lots more to do, but we think a diverse and inclusive board will help us better reach our aim of global raptor conservation.