Golden Eagles are the largest eagles in North America.

Aquila chrysaetos

67-year annual average: 52

1992-2001: 94

Record year: 144 (1998)

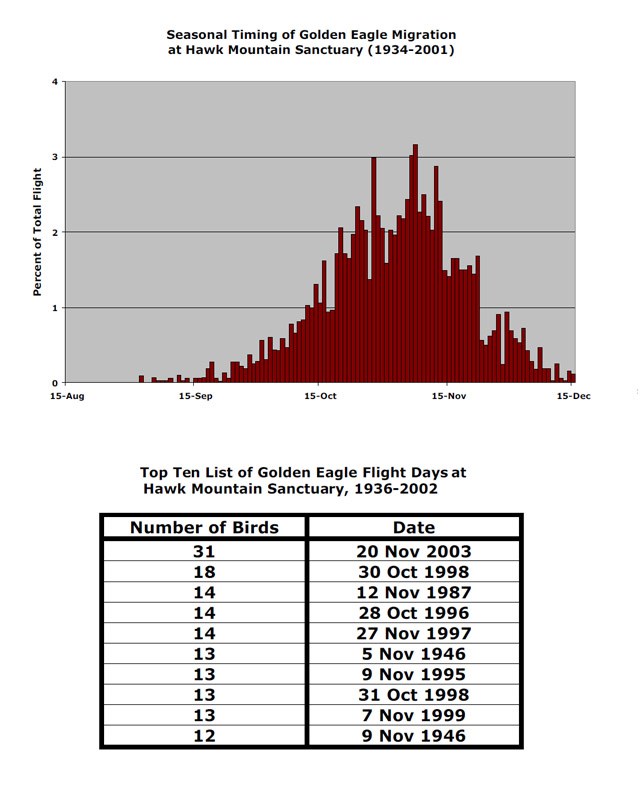

Best chance to see: Early November.

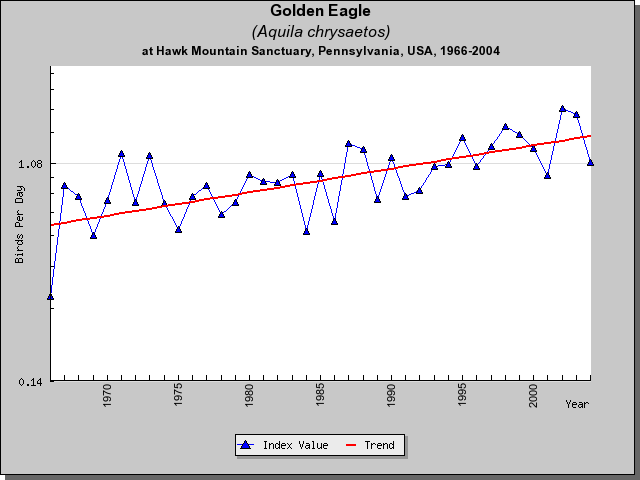

Longterm trends: Decreased in 1940s, 50s and early 60s. Increasing since late 1960s.

A.K.A. Ring-tailed Eagle

Field marks: Large raptor, with long, plank-like wings, which are sometimes held above the horizontal in a shallow dihedral. Overall impression is of an enormous buteo. Adults are usually uniformly dark, except for a “golden” nape, and “golden” feathering along the middle of the upper wings. Juveniles may have distinct white wing patches at the base of the primaries and white at the base of the tail.

Flight behavior: Typically migrates alone. Soars using updrafts and thermals; occasionally flaps and glides while migrating. Strong, stable flight, even in high winds.

What Size is a Golden Eagle?

- Wingspan6'-7'3"

- Length2'3"-2'9"

- W-L ratio2.6:1

- Weight7-14 lbs

Raptor Bites

- Belongs to the family Accipitridae, a group of 224 species of hawks, eagles, vultures, harriers, and kites.

- Are the largest eagles in North America, and considered by many the most formidable of all of the North American raptors.

- Are found in North America, Europe, and Asia.

- Although they prefer to eat live prey, Golden Eagles will eat carrion.

- Occasionally take prey as large as deer and antelope.

- Dominate other raptors in disputes over food.

- Can soar in winds of up to 100 mph.

- The territories of Golden Eagles sometimes exceed 25 square miles.

- Sometimes build several nests before choosing one to use.

- Many Golden Eagles are electrocuted each year while perch-hunting from utility lines in treeless areas.

Seasonal Count – from North Lookout – 1934 to Date

Introduction

The Golden Eagle is a large, powerful raptor named for the golden-colored feathers on its head and neck. The species is found throughout the Northern Hemisphere, including North America, Europe, Asia, and northern Africa. These Eagles prefer undisturbed, open landscapes in mountainous areas. The species is most common in regions that provide open spaces for hunting and cliffs for nesting. In North America, Golden Eagles are far more common in the West than in the East. One of the largest and most powerful raptors in North America, these Eagles have engendered sentiments of admiration, fear, and hatred. Historically and today, people pose the greatest threat to Golden Eagles. Native Americans once killed large numbers of eagles for use in ceremonies. In the American West, large numbers of eagles were shot by ranchers who believed they were regularly killing sheep. In1936, aerial shooting from helicopters began. In Texas and New Mexico, ranchers and others are thought to have killed 20,000 eagles between 1940 and 1962. In1962, the Bald Eagle Protection Act was amended to include the Golden Eagle, and adults, their young, eggs and nests are now protected in the United States. In 1972,the species received protection in Canada, the United States, and Mexico under the Migratory Bird Treaty Act.

Identification

The Golden Eagle is a large, dark raptor with golden-colored feathers on its crown and nape. Eagles acquire adult plumage at four to five years of age. Adult Eagles are largely dark brown with dark-barred grayish tails. Immature Golden Eagles are mainly brown with white patches at the base of their flight feathers, and a white tail with a wide, dark sub-terminal band and a thin, white fringe. Subsequent molts have increasingly less white both on the wings and tail. Eagles soar with their wings in a slight dihedral or “V” shape. In active flight, the species flies with slow, powerful wingbeats and usually glides briefly after flapping six to eight times. Golden Eagles sometimes dive at speeds that approach those of large falcons. The Golden Eagle has a smaller beak and a somewhat smaller head than the Bald Eagle.

Breeding Habits

Golden Eagles typically nest in open or semi-open habitats including shrubland, grassland, farmland, woodland, coniferous forest and tundra. The species tends to avoid heavily forested areas. Nests are built on cliffs, in trees, on embankments, on man-made structures, and on the ground. Most nests are close to hunting areas, and generally afford a good view of the surrounding area. Nests in trees usually are in one of the largest trees in a stand. Nests are constructed mainly of thick branches and nest-building begins one to three months before egg-laying. Both mates share in nest-building prior to incubation, and both add greenery to the nest throughout the nesting period. Females deliver the bulk of the nesting material that is added during brooding. Non-migratory pairs sometimes add nesting material outside of the breeding season. Pairs commonly maintain two or three alternate nests within their territory. Golden Eagles often reuse their nests, sometimes for decades. Nests can grow considerably over multiple years, and new nests are not always used in the year they are constructed. Most Golden Eagles begin breeding when they are four or five years old. Golden Eagles are monogamous and pairs are believed to mate for life. Even so, when one member of the pair dies, the remaining eagle quickly finds a new mate. In non-migratory populations, pairs often stay together for the entire year. Before nesting, pairs defend their territory, perform aerial displays, vocalize, and bring materials to the nest. Courtship includes mutual soaring and circling, undulating flights, chases, dives, and mock attacks. Although undulating flight displays are performed during courtship, such flights are believed to function primarily as territorial displays. During “sky dancing,” males repeat a series of steep dives and ascents, and up to 20undulations may be incorporated into a single display. During “pendulum flights,” individuals dive, climb back to their original height, turn over, and repeat the same course. The species has a prolonged nesting period of six months or more and pairs sometimes forgo nesting when food is scarce. Golden Eagles usually lay two eggs. The second egg is laid three to four days after the first, and siblings hatch asynchronously. The smaller chick typically receives less food and often only the older, dominant nestling survives. Conflicts between siblings are common and siblicide (one nestling killing the other) sometimes occurs, particularly when food is scarce. During the 43- to 45-day incubation period, females do most of the incubating and also are responsible for brooding the nestlings. Females brood the nestlings continually for 10 days after hatching. The male provides almost all of the food for the female and the young until the nestlings are about two weeks old. Thereafter, the female gradually spends less time brooding and assists the male in providing food for the young. Although both parents deliver food to the nest, only the female feeds the nestlings directly. The nestlings begin to tear apart their own food when they are 34 to 37 days old. Fledging occurs as early as 45 days and as late as 84 days. Most young are not capable of sustained flight until they are at least 64 days of age and some individuals depend on their parents for food for up to six months after fledging. Young from migratory populations are likely to become independent earlier than those from sedentary populations.

Feeding Habits

The Golden Eagle is an agile predator that hunts both from perches and on the wing. In flight, the species searches for prey while soaring and during low contour flight. Weather, topography, and the type of prey being hunted determine which hunting method is used. Contour hunting appears to be the Golden Eagle’s primary hunting strategy. Pairs sometimes hunt cooperatively, particularly for large prey items. Most prey is captured on the ground, but birds also are caught in the air. Large prey is usually fed on at the kill site. Eagles sometimes gather at large carcasses and at such times the dominant individual feeds while subordinates wait. The Eagle is an opportunistic predator that feeds on a variety of species, and whose diet varies geographically and temporally. They prefer to feed on small- to medium-sized mammals. In North America, rabbits, hares, ground squirrels, prairie dogs and marmots are the most commonly taken prey items. During the breeding season, Golden Eagles feed primarily on mammals, secondarily on birds, and less frequently on reptiles and fish. Birds most often taken include pheasants, grouse, and partridges. In some areas waterfowl are an important prey item. Although they favor small prey, eagles are powerful predators that sometimes catch prey larger than themselves including bighorn sheep, mountain goats, deer, pronghorn, caribou, seals, coyotes, badgers, and bobcats. Large avian prey include Wild Turkeys, swans, cranes, Great Blue Herons, and Ospreys. The species regularly feeds on carrion, especially in winter. Although Golden Eagles rarely prey on domestic animals, they often are viewed as a threat to livestock.

Migration

The Golden Eagle is one of 26 North American raptors that are partial migrants. Golden Eagles living at the northern end of the species range are more likely to migrate than are individuals breeding farther south. Although some northern breeders travel more than 5,000 km between their breeding and wintering grounds, most migrants are short- or moderate-distance migrants. At low latitudes, pairs tend to be sedentary. Sedentary eagles sometimes vacate their breeding grounds in years when food is scarce. Like other raptors, Golden Eagles begin migrating across a broad front, but tend to concentrate along leading lines as they move south. Golden Eagles are observed in largest numbers along north-south oriented mountain ranges where they soar on mountain updrafts, and near the Great Lakes. The species typically avoids lengthy water-crossings. In North America, migrating Eagles concentrate along the Appalachian Mountains in the East and Rocky Mountains in the West. These Eagles generally migrate alone, or in small flocks of two to five birds. Migrants travel at speeds up to 50 to 55 kilometers per hour. In autumn, immature Golden Eagles leave the breeding grounds earlier than adults. In spring adults migrate before immature birds. The species frequently hunts on migration. At Hawk Mountain Sanctuary, peak numbers of Golden Eagles are seen on the day after the passage of a cold front. The majority of the Golden Eagle flight at Hawk Mountain occurs in November. The long-term average count at Hawk Mountain (1934-2002) is 54, and the average count for the past 10 years (1993-2002) is about 100. In autumn 2003, 159 Golden Eagles were counted at Hawk Mountain and the Sanctuary recorded its highest one-day count of 31 Golden Eagles on November 20, 2003.

Conservation Status

The current world population of Golden Eagles is believed to exceed 120,000 birds. In North America, the number of breeding Golden Eagles is estimated to be between 40,000 and 50,000 individuals. Although some populations are declining regionally, numbers appear to be stable or increasing globally. Golden Eagles have few natural enemies, and people, both indirectly and directly, remain the greatest source of mortality for the species. Historically, Golden Eagles suffered from acts of direct persecution including shooting, trapping, and nest destruction. Today, the species is protected in North America, and although incidents of direct persecution continue to occur, they are uncommon. Other sources of mortality include electrocution, collisions with vehicles, powerlines, and other man-made structures including wind turbines, and poisoning. Golden Eagles are poisoned when they visit baited carcasses targeting mammalian predators and when they feed on carcasses containing lead shot. The species feeds primarily on mammals, and its populations were not affected by the widespread use of organochlorine pesticides. Human disturbance around nests can lead to nest abandonment. Habitat changes including urbanization, agricultural development, wildfires, and mining activities decrease available habitat and reduce prey populations. In eastern North America, reforestation may result in the loss of suitable habitat.

| BWHA Trends | ||

| Year Range | Trend Value | P |

| 1970-1980 | 2.1 | <0.0001 |

| 1974-2004 | 2.1 | <0.0001 |

| 1980-1990 | 2.1 | <0.0001 |

Golden Eagle Reading List

DUNNE, P., D. SIBLEY, AND C. SUTTON. 1988. Hawks in flight. Houghton Mifflin Company, Boston, Massachusetts.

FERGUSON-LEES, J. AND D.A. CHRISTIE. 2001. Raptors of the World. Houghton Mifflin Company, Boston, Massachusetts.

JOHNSGARD, P.A. 1990. Hawks, eagles, and falcons of North America. Smithsonian Institution Press, Washington, D.C.

KOCHERT, M.N., K. STEENHOF, C.L. MCINTYRE, AND E.H. CRAIG. 2002. Golden Eagle (Aquila chrysaetos). No. 684 in The Birds of North America (A. Poole and F. Gill, Eds). The Birds of North America, Inc., Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

WEIDENSAUL, S. 1989. North American birds of prey. Gallery Books, New York, New York.

WHEELER, B.K. 2003. Raptors of eastern North America. Princeton University Press, Princeton, New Jersey.

WHEELER, B.K. AND CLARK, W.S. 1999. A photographic guide to North American raptors. Academic Press, San Diego, California.