Turkey Vultures are the most migratory of all vultures.

Carthartes aura

67-year annual average: 92

1992-2001: 206

Record year: 367 (1999)

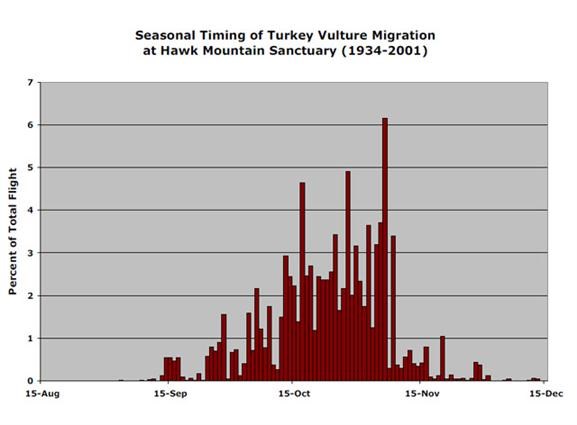

Best chance to see: Early November.

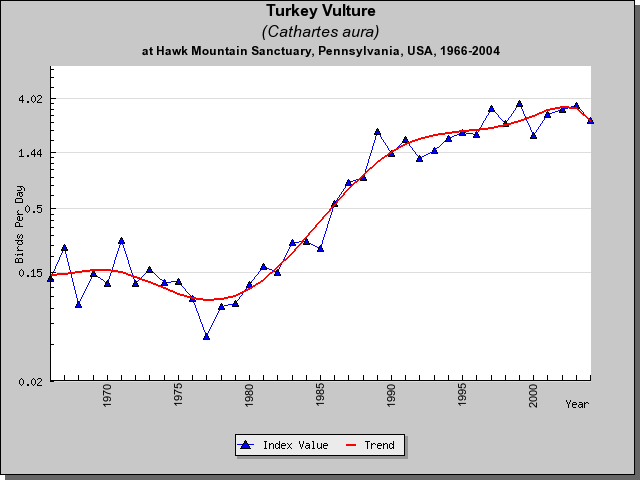

Longterm trends: Increasing slowly, probably in response to northward expansion of breeding range into southern Canada.

A.K.A. T.V., Turkey Buzzard

Field marks: Large, dark brown, heavy-bodied and small-headed, carrion-eating bird, with a longish tail and two-toned underwings. Wings held above the horizontal in a strong dihedral, or “V.”

Flight behavior: Typically migrates in flocks of up to hundreds of birds. Soars extensively on migration. Often rocks from side to side while soaring. Rarely flaps. Uses thermals; rarely migrates early in the morning or late in the afternoon. Local populations present through early December.

Click below to view flyers summarizing the turkey vulture's habitat and nesting behaviors, as well as guidelines for landowners that may encounter forest nesting raptors:

Turkey Vulture Habitat & Nesting Landowner Guide to Protecting Nesting Raptors

What Size is a Turkey Vulture?

- Wingspan5'6"

- Length2'2"-2'8"

- W-L ratio2.4:1

- Weight3.5-5 lbs

Raptor Bites

- Belong to the family Cathartidae, a group of 7 species of New World Vultures.

- Are so named because their red, featherless heads resemble those of Wild Turkeys (Meleagris gallopavo).

- Although they feed almost exclusively on carrion (dead animals), they sometimes take live prey.

- Are the most migratory of all vultures.

- Their plumage is dark brown, not black.

- When flying, Turkey Vultures, hold their wings in a “V” above their backs, creating a slight dihedral that stabilizes their flight in turbulance.

- Often roost in groups of several hundred birds.

- Have an acute sense of smell, which enables them to find carrion by both smell and sight.

- Communicate vocally in hisses and grunts.

- Nestling Turkey Vultures projectile vomit to defend themselves.

- Are unable to carry off their carrion.

Seasonal Count – from North Lookout – 1934 to Date

Introduction

The Turkey Vulture is so named because its red, featherless head resembles that of the Wild Turkey. The species is a common, well-known, and readily recognizable bird that ranges across southern Canada to southernmost South America. Vultures are the most widely distributed of all seven species of New World vultures. Some experts believe that Vultures and other New World vultures are more closely related to storks than to other raptors. Vultures are masters at soaring, and once above the canopy, rarely flap their wings. When soaring, Vultures hold their wings in a dihedral, or “V” shape, above their backs, and often rock side-to-side in the wind. The species is quite social, and individuals often fly together in flocks or “kettles” both when migrating and when searching for food. Outside of the breeding season, Turkey Vultures often roost together with Black Vultures at communal roosts, sometimes by the hundreds. Like most vultures, Turkey Vultures feed almost entirely on carrion, which they find by both smell and by sight. Other vultures, such as Black Vultures, lack a keen sense of smell and often follow Turkey Vultures to carcasses.

Identification

The Turkey Vulture is a large, eagle-sized bird with a wingspan that approaches six feet. The species is dark blackish-brown overall except for the undersides of its flight feathers, which are silver-gray. In flight, the Vulture’s featherless head appears small for the bird’s size. Adult Vultures have red heads and bonecolored beaks. Recently fledged juveniles have gray heads and dark beaks.

Breeding Habits

Turkey Vultures occur in a variety of open and forested habitats. Unlike Black Vultures, Turkey Vultures typically avoid urban and suburban areas. In North America, the species breeds in farmlands, rangelands, forests, and low-elevation mountains. Turkey Vultures do not build nests, but rather lay their eggs in dark recesses in ledges, caves, crevices, and hollow logs, as well as on the ground. Turkey Vultures also nest in the abandoned stick nests of birds, in mammal burrows, and in abandoned buildings. The species is monogamous, and evidence suggests that pairs remain together until one member dies. Existing pairs return to and reuse nesting sites year after year. For several days to several weeks prior to egg-laying, the pair spends time sitting together at the nest. Vultures perform aerial courtship displays during which one bird follows the other and precisely mimics the lead bird’s flight path. Flight displays are usually brief, although occasionally they are repeated for several hours. Although clutches can range in size from one to three eggs, Vultures generally lay two eggs. Both parents share the task of incubation, which lasts for about five weeks. Males and females also take turns brooding the young, which are brooded continually for the first five days. Thereafter, the parents spend less time brooding. Both parents feed the young by regurgitation, either directly into a begging nestling’s gaping mouth or on the ground next to the nestling. Young Vultures fledge at 60 to 80 days of age. For one to three weeks after their first flight, fledglings perch and roost at the nest site and continue to be fed by their parents. Thereafter fledglings slowly explore the area around the nest site, and by the time they are 12 weeks old, they have dispersed from the area.

Feeding Habits

Turkey Vultures feed almost entirely on carrion and human garbage. Although on rare occasions Turkey Vultures catch live prey, including young or sick birds and mammals, Black Vultures kill live prey more frequently, and accounts of Turkey Vultures eating live prey often involve mistakenly identified Black Vultures. Vultures also eat plant material including pumpkins, coconuts, juniper berries, and grapes. Mammals serve as the predominant source of carrion, but dead birds, reptiles, amphibians, and invertebrates also are consumed. Vultures prefer to eat “freshly” dead carrion, but they also will feed on decaying carcasses. The species lacks powerful feet to carry its food, and most carrion is consumed where it is found. Turkey Vultures compete for carrion with Black Vultures in North America, and with Black Vultures, Lesser Yellow-headed Vultures, Greater Yellow-headed Vultures, King Vultures, and Andean Condors in Latin America. On their wintering grounds in Venezuela, migrant Turkey Vultures from North America displace smaller, resident Turkey Vultures from preferred feeding sites. Because the Vultures find food using their sense of smell as well as by sight, they are able to locate carcasses on the forest floor beneath dense forest canopies. In North America, the Turkey Vulture is the only vulture with a highly developed sense of smell. Black Vultures, are more aggressive than these Vultures and will often follow them to carcasses and displace them from the carcass.

Migration

The Turkey Vulture is one of 26 North American raptors that are partial migrants. Northern populations of these Vultures tend to be highly migratory whereas southern populations are less migratory (sedentary). During migration northern birds “leap-frog” over and winter farther south than southern birds. In North America, these Vultures are more migratory in the West than in the East, and many western birds are long-distance migrants that spend the winter in Central and South America. Turkey Vultures soar and glide extensively on thermals and mountain updrafts while migrating. As a result, migrating Turkey Vultures concentrate along leading lines including mountain ridges, shorelines, and coastlines. Because they rely on thermals and mountain updrafts to provide them with sources of lift, these Vultures typically avoid crossing large bodies of water that would require them to engage in long bouts of powered flight. The species usually does not migrate on rainy or completely overcast days when thermals do not form. These Vultures migrate in flocks that range in size from several birds to several thousand birds. Flock size increases substantially in the tropics. In Mexico and Central America, for example, flock size often exceeds 10,000 birds. Flocks of migrating Turkey Vultures often commingle with those of Broad-winged Hawks and Swainson’s Hawks. About 200 migrating Turkey Vultures are seen at Hawk Mountain Sanctuary each autumn and the Turkey Vulture flight peaks in early November.

Conservation Status

The current world population of this New World species almost certainly exceeds five million birds. Most populations of this adaptable species appear to be thriving. In general, the this Vulture’s beneficial role as a scavenger is recognized, and the species is not persecuted. Unfortunately, this was not always the case. In the past, these Vultures were shot because ranchers and farmers mistakenly believed that they spread diseases and contaminated watering holes for livestock, although there is no evidence to substantiate this claim. These Vultures also have been blamed and persecuted for livestock losses they were not responsible for. Individuals, historically and currently, are sometimes mistakenly poisoned at baited carcasses and are killed or injured in steel leg-hold traps set for mammals. Environmental contaminants including lead, mercury, and insecticides can poison these Vultures. Overall numbers of Turkey Vultures remained stable during the DDT era of the 1940s to the early 1970s, even though eggshell-thinning and reduced reproductive success due to pesticide contamination occurred in some areas. Turkey Vultures frequently feed on roadkill, and collisions with automobiles are a common source of mortality in some areas. The species also collides with aircraft; between 1989 and 1992, Turkey Vulture collisions with United States Air Force aircraft resulted in two human deaths, three airplane crashes, and a loss of more than 21 million dollars.

| BWHA Trends | ||

| Year Range | Trend Value | P |

| 1970-1980 | ||

| 1974-2004 | 7.0 | <0.0001 |

| 1980-1990 |

Turkey Vulture Reading List

BILDSTEIN, K. L. 2006. Migrating Raptors of the World. Cornell University Press.

DUNNE, P., D. SIBLEY, AND C. SUTTON. 1988. Hawks in flight. Houghton Mifflin Company, Boston, Massachusetts.

FERGUSON-LEES, J. AND D.A. CHRISTIE. 2001. Raptors of the World. Houghton Mifflin Company, Boston, Massachusetts.

KIRK, D.A. AND M.J. MOSSMAN. 1998. Turkey Vulture (Cathartes aura). No. 339 in The Birds of North America (A. Poole and F. Gill, Eds). The Birds of North America, Inc., Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

SNYDER, N. AND H. SNYDER. 1991. Raptors: North American birds of prey. Voyageur Press, Stillwater, Minnesota.

WEIDENSAUL, S. 1989. North American birds of prey. Gallery Books, New York, New York.

WHEELER, B.K. AND CLARK, W.S. 1999. A photographic guide to North American raptors. Academic Press, San Diego, California.