Urbanite Peregrines on the Move

Posted on June 27, 2019 in Science

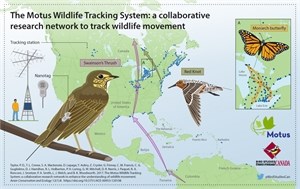

Hawk Mountain is assisting the Pennsylvania Game Commission in deploying nanotags on peregrine fledglings from several nests in the state, including one appropriately located on top of the Rachel Carson building in Harrisburg. This is the first year for the project, with eight falcons having been tagged thus far. These birds will be tracked using the Motus (Latin for “movement”) wildlife tracking system through which a series of receiving towers detect the movements of tagged birds passing nearby.

The Motus website expresses the benefits of this system well, noting that “automated radio telemetry harnesses the collective resources of many independent researchers into a much larger collaborative effort that expands the scale and scope of everyone’s work while maximizing scarce research and conservation dollars.” The Motus system is tracking birds, bats, and even large insects, scanning for signals 24 hours a day. The Peregrine falcon nanotags have 500 days of battery life, providing an optimal time frame through which we can investigate the movements of young falcons during their most vulnerable stage of life. Nanotags are much lighter and cheaper than other types of tracking devices, and therefore serve as the ideal device for tracking young peregrines.

By helping with the Game Commission’s study, we hope to investigate dispersal and survival rates of peregrine falcons fledging from their natal grounds, both of which are poorly understood.

Another element of peregrine ecology that has yet to be unveiled is the comparative fledging success between urban nest sites and natural cliff faces. Historically, peregrines were found nesting primarily along cliffsides. However, after World War II the infamous insecticide DDT made its way into the food web, and consequently wreaked havoc on a variety of species including predatory birds. Upon ingesting high enough levels of DDT, peregrine falcons were unable to produce thick enough egg shells to support the parent’s weight during incubation, resulting in failed reproduction. The effects of DDT continued for three decades, and by 1964, nesting peregrines were extinct in the eastern United States. Conservationists were faced with the choice of watching this valued species dwindle away or initiating captive breeding programs. At this point, the American population of peregrines was at 12% of its original population. Through the collaborative efforts of the Peregrine Fund, the Midwestern Peregrine Falcon Restoration Project, the Canadian Wildlife Service, falconers, and may other individuals and organizations, a recovery program was developed and carried out, resulting in the release of 6,000 captive-raised peregrines throughout the U.S. DDT was banned in 1972 following Rachel Carson’s highly influential book Silent Spring which awoke the public to the detrimental consequences of DDT on the natural world and human health. Carson, who visited Hawk Mountain’s North Lookout during her research, fought hard against the opposition of agricultural interests and in the end prevailed, securing a better future for raptors and countless other species who were threatened by insecticides.

Now, following the recovery of peregrine populations across their range, we have the unique opportunity to assess a new era of fledglings. Not all of the captive releases went to natural sites; peregrines were known to hunt in cities and surprisingly, seemed capable of nesting amidst the high steeples and relatively predator-free habitat of the cityscape (and let’s not forget the cornucopia of chunky pigeons available around every corner).

Even so, Patti Barber, endangered species biologist with the PA Game Commission says that falcons raised in urban landscapes return less often to breed than do their counterparts raised on natural cliff faces. By assessing the movement ecology of these urban-fledged chicks, we may be able to gain insight into why this is. The city is a busy place, and for a young inexperienced bird, natural instinct may not be enough to ensure survival. Currently in both Harrisburg and Allentown there are self-organized volunteer groups that keep vigilant watch over two nests, rescuing uncoordinated fledglings as they attempt their first forays into the city, or simply fall from the nest. As one would imagine, a city is filled with potential danger for nestlings, and these dedicated volunteers are ready and willing to assist. At least three of the four recently fledged chicks from the Rachel Carson Building were rescued.

In total, the PA Game Commission has 20 nanotags to deploy, ideally within the next two years. This Spring, Hawk Mountain’s Senior Scientist Dr. JF Therrien traveled with Patti Barber to Harrisburg to assist in tagging “Red,” the nestling who received the red leg band. Red, along with three other fledglings (“Yellow,” “White,” and “Blue”) are now being tracked. We look forward to hearing from then via the Motus network and watching their travels from afar!

Including this year’s tagged chicks, there are now eight Pennsylvania-born peregrines sporting nanotags. Elsewhere in the country, city-nesting peregrines are receiving more and more attention as they adapt to the benefits of city life. 24-hour light, for example provides more opportunities for them to see and catch their prey. City buildings also absorb heat during the day, resulting in thermal production which allows the falcons to save energy as they float with seemingly little effort above the skyline, searching for pigeons, migratory songbirds, and waterfowl.

There are certainly downsides to raising chicks on a skyscraper, but there are benefits too. With these new research methods, we hope to assist the Game Commission in identifying how this species is adapting to increasingly human-dominated landscapes.

To learn more about the Motus tracking system, visit https://motus.org. For a look at peregrine falcons nesting in Chicago, watch this short PBS film produced by Sophie Meyjes and Lucy Smith.

And to see migrating peregrine falcons as they make their way south, visit Hawk Mountain in the Fall! We hope to see you.