Living on the Edge

Posted on November 04, 2019 in Science

During September, visitors to Hawk Mountain Sanctuary look forward to the annual migration of broad-winged hawks on their journey to Central and South America. This raptor species is known for their flocking behavior during migration, a jaw-dropping spectacle called kettling. On days with large kettles, hundreds of these graceful predators pass overhead, leaving counters simultaneously exhausted and invigorated by the end of their shift. In addition to utilizing Pennsylvanian ridges during migration, broadwings also nest within the state. Unfortunately, this species exhibited a significant decline between 2004 and 2013 at several hawk watch sites along the Atlantic and Appalachian flyways. The trend was further confirmed through the Pennsylvania Breeding Bird Atlas, and in 8 northeastern states, the U.S. Geological Survey deemed them a “Species of Greatest Conservation Need.” In Pennsylvania alone, there was a 16% decrease in the breeding range between the 1980s to the late 2000s, particularly in southern counties.

To further understand the change in distribution of broad-winged hawks, Dr. Laurie Goodrich sought funding from Pennsylvania State Wildlife Grants program within the PA Game Commission, as well as private donors, to fund a master’s student project. Former trainee Rebecca McCabe agreed to take on the project for her M.S. degree, working with Dr. Terry Master of East Stroudsburg University and assisted by Goodrich and field assistant Zach Bordner. Together, they composed a multi-year, landscape-scale investigation into measurable life history traits of broad-winged hawks. This September, their results were published in the Journal of Raptor Research.

Using nest cameras and on-the-ground observations of nesting behavior, the research team analyzed differences in parental behavior between three separate landscape types. The goal of this approach was to assess whether forest fragmentation has an impact on nesting success, given that broad-winged hawks show a preference for unbroken, continuous tracts of forest.

Forest loss and fragmentation result from human activities such as urban expansion, timber harvest, clearcutting, and other forms of development. Between 1973 and 2000, these activities played a significant role in the available habitat for forest-dependent birds throughout the eastern United States. Fragmentation, or the dividing of forest, has both direct and indirect impacts on forest-dwelling raptors. One side effect is the creation of more forest edges. This forces broad-winged hawks to nest nearer to edges where their predators, such as the Great Horned Owl, prowl. More edge habitats could also mean increased competition between species seeking nesting territories, potentially further displacing broadwings. Forest cover alterations can also influence abundance and composition of small mammals, birds, and amphibians that make up most of the broad-winged hawk diet. For example, staple prey species like the eastern chipmunk struggle to survive when forest cover is reduced.

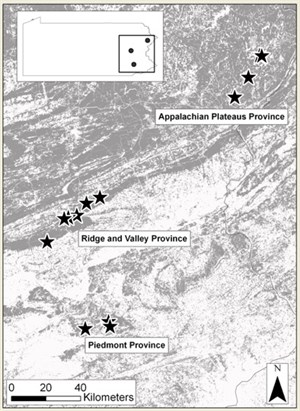

This study compared nesting behavior amongst three provinces within the state, all experiencing varying degrees of forest fragmentation. These three focal areas were Ridge and Valley, the Piedmont, and the Appalachian Plateau. The Ridge and Valley is 59% forested with contiguous forested areas, linear ridges, and very developed valleys and agricultural land. Even so, forest cover in this region has been relatively stable from the 1990s to 2005. The Piedmont is 32% forested with highly fragmented forests interspersed with suburban developments. This region experienced a 6% decrease in forest cover during the same 15-year time frame. The Appalachian Plateau is 71% forested, contains many areas of uninterrupted forest, and has undergone an increase in forest cover by about 2.4% during those 15 years.

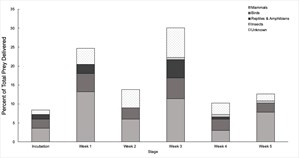

Interestingly, there was no clear difference detected in parental behavior between the three landscapes. Over the course of 1,357 observation hours on 13 different nests, the research team found that the composition, delivery rate, diversity of prey and nest materials, as well as attendance of parents to the nest, all remained relatively similar. This implies that broad-winged hawks can thrive in a variety of forest types and adjust to available resources as necessary, at least during the nesting season.

Researchers also noticed a strong representation of eastern chipmunks in prey deliveries to the nest at above 16% of total prey deliveries. The presence of parents at all nests decreased significantly from week 1 of the nestling period to week 2, and continued to decrease as the nestlings developed, reflecting a similar trend found in broadwing nests in Puerto Rico. As nestlings develop, they become capable of thermoregulating for themselves and require less immediate attention from their parents. This means dense forest cover may be an important factor in nesting success, given that these parents spend a large portion of their time away from the nest, foraging. With less cover, the nestlings are more exposed. The team observed a variety of nesting materials being brought to the nests, including fresh oak and hemlock sprigs, dead sticks, and bark. Interestingly, fresh sprigs were often delivered to the nest after the young were fed, supporting a proposed hypothesis that this plant material may contain volatile compounds that help deter insects.

While the exact causes of decline for broad-winged hawks in Pennsylvania have yet to be uncovered, this study offered valuable baseline information on a forest raptor that, McCabe notes, hasn’t been studied intensively since the 1980s. As she reflected on her experience in the field, she emphasized the benefit of quality natural history observation, noting that this study empowered her to recognize the value of simplified life history documentation. She feels privileged to have partaken in work that will affect management of broad-winged hawk habitat and inform people about the relationship between these beloved hawks and the changing landscapes they journey between.

For more information on the natural history of broad-winged hawks, visit hawkmountain.org/broadwing.

Funding for this study was provided by PA State Wildlife Grants from the PA Game Commission, The Kittatinny Ridge Coalition, PA Dept of Conservation and Natural Resources, ATAS, Inc., and several key private donors.

To support the future of Hawk Mountain's broad-winged hawk research, including satellite tracking and tagging, contact Dr. Laurie Goodrich at 570-943-3411 ext 106 or donate now.