Over the Coast and Far Away | Tracking Peregrine Falcons

Posted on in In the Field by Hawk Mountain

TRACKING ARCTIC PEREGRINE FALCONS DURING AUTUMN MIGRATION.

As a component of Hawk Mountain Sanctuary's commitment to study birds of prey worldwide, we have been involved in studying all ecological aspects of birds of prey in the Arctic. Those species include the well-known snowy owls, rough-legged hawks, and peregrine falcons for which we assess breeding and survival rates, as well as detailed studies of movement ecology.

To achieve this, our projects involve the use of telemetry transmitters, high-tech devices that allow us to track in almost real-time the movements of individual birds over consecutive years. For more than a decade now, we have been active in equipping several snowy owls with such units. More recently, we added the rough-legged hawk on our list of tracked species, and we were aiming to do the same with peregrine falcons.

Earlier this year, our longtime collaborators from the Max Planck Institute for Ornithology in Germany agreed to provide us with 8 transmitters to be deployed on hatch-year peregrine falcons from the Arctic. However, the units were only to be ready in August which was too tight for us to deploy them in Arctic breeding grounds.

This is when the Cape May Raptor Banding Project (CMRBP) and its president Paul Napier came in. I remembered Paul coming to Hawk Mountain to give one of the spring lectures, in which he depicted the CMRBP and the amazing number of birds they were banding annually for more than 40 years. Seeing that they were getting lots of Arctic peregrine falcons passing through Cape May during the autumn migration, I asked him: would the CMRBP be interested in having me installing units on some of the peregrines they catch? His answer was both quick and positive: how many units can you bring with you?

So after making all arrangements, we were off to Cape May in early October because this is the time when the highest numbers of peregrine falcons are seen and trapped every year. While the team of experienced trappers has historically been pretty efficient, they can only capture the birds that come down to the region. On light or unfavorable migration days, the trapping success obviously decreases.

But Paul and his colleagues were right; they do catch lots of birds. During the first 2 days, their team trapped 3 peregrines on which we installed tracking units. Overall, in 6 days, we succeeded in installing units on 6 hatch-year peregrines.

That was already a success, but then, I still had 2 additional units that I decided to bring along with me as I was going back to Cape May in mid-October to attend the 50th annual Raptor Research Foundation meeting. The meeting brought an impressive amount of high quality talks and plenary sessions, but the most exciting to me was to receive a call from one of the CMRBP trapper saying that they were catching peregrine falcons on the first day of the meeting. So, we left the meeting twice on October 17th to go and install the remaining 2 units. In less than 8 days of field work, we had installed 8 units on migrating peregrine falcons!

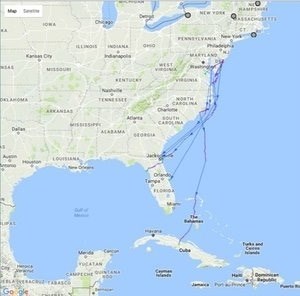

Now the results are just starting to come in, and it is already very exciting. Continuing down the Atlantic Coast, almost all tracked birds reached North Carolina's Outer Banks islands and then engaged in over water migration flight to reach Florida and even Cuba in just a few days after being released in Cape May, New Jersey. We have yet to analyze the details of those oversea travels (speed, time of day, presence of tailwinds, etc.), but it is safe to say that migrating peregrine falcons do not avoid water crossings altogether, which changes our perception of their movement ecology.

More exciting results are to come in the next months, and we will keep you posted.