Fieldwork in the Falklands

Posted on February 25, 2013 in Science

Visit the Blog, The Vulture Chronicles

Learn more about Hawk Mountain's global research projects

Caracaras ripped my seat

Posted by Keith L. Bildstein, Ph.D.

Sarkis Acopian Director of Conservation Science

24 February 2013

Having studied Striated Caracaras–or Johnny Rooks as they are often called–on the Falkland Islands for three years, I have steadfastly defended “my” species against their “flying devils” reputation. They are in no way “bad birds,” I have told people, but rather are merely curious and, at times, a bit mischievous, but certainly not mean spirited. But after what happened earlier today I may need to change, or at least temper, my feelings toward these birds.

Thanks to supporters Joe Jehl, Jr. and Racey Gilbert, I was able to buy a 4×4 ATV to complete the road surveys on 49-square-mile Saunder’s Island last year, and my first “quad-trip” from the farm settlement on the island to the Gentoo Penguin colony this February went off without a hitch. The ten-mile trek across rugged and rocky terrain had taken me more than an hour to complete, and I was eager to survey the penguin colony for color-banded caracaras as part of my ongoing research on their movement ecology on and beyond the island.

Three un-banded Johnny Rooks met me and the quad at the gate to the penguin colony and I decided to take my ignition key with me just in case the birds had a mind to take my vehicle for a spin. I then went off on foot for my one hour survey at the colony.

Forty minutes later, when my quad was once again in view, I noticed that five Johnnies were hopping all over it, and that at least one bird was pulling at the vehicle’s black naugahide seat. I was still more than half a kilometer away and downhill from the quad, and I decided to continue my search for banded Johnnies and deal with un-banded individuals at the quad once I was done.

When I closed to within 100 meters of the vehicle, I could see that the birds already had shredded the front edge of the seat cover and that two juvenile Johnnies were alternately pulling out the foam-rubber cushioning and calling out to the others to join in the fun.

I often tell people that the strongest muscles in a Johnny Rook are its neck muscles, and strong neck muscles enhance their ability to quickly pull meat from penguin carcasses during the feeding frenzies they engage in. I was now witnessing how they managed to keep those muscles in shape: in less than an hour my relatively new quad had become an exercise machine, the avian equivalent of a stair-master for the neck.

I sprinted the last 50 meters to the quad and surveyed the damage. Dozens of bite-sized pieces of foam rubber were scattered about the machine, as were several long strips of shiny new black naugahide. The dash board was missing several buttons, including the one that I use to reset the vehicle’s odometer to record distances traveled on my quad surveys, and the area around the ignition lock had been tampered with.

Looking down at the three remaining birds, I proudly extracted the quad key from my jeans and showed it to them. “I outsmarted you guys,” I said to myself and placed the key in the ignition slot. But when I turned it, nothing happened. The horn worked just fine, but I couldn’t start the quad, and the idea of a ten-mile walk back to the settlement crossed my mind.

Not fun and certainly, more than a bit embarrassing.

Methodically inspecting the quad’s heavily festooned handle bars from left-to-right helped me solve the mystery. The Johnnies has pulled my emergency stop cord from its mooring and had hidden the critical connecting rubber plug under the cowling that surrounded the quad’s steering column. In less than a minute I reassembled the safety contraption, started the vehicle, took off toward the settlement.

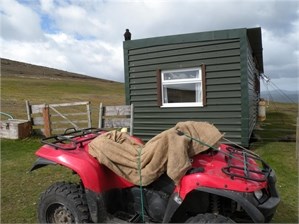

I spent the rest of the afternoon reupholstering my seat cushion with foam-rubber from my camera’s Pelican Case and an ever-handy roll of duct tape. I then asked my Falkland Island hosts for suggestions on how better to protect my quad from my birds. A heavy-weight burlap bag appeared, together with a handful of bungee cords. Since then, cloaking my quad with burlap has prevented the Johnnies from destroying it.

The take-home message: Flying devils? No, not really.

It isn’t every day that a study species teaches a biologist how to take care of his equipment. In fact, I probably owe the Johnnies a favor for setting me straight on how to keep my quad intact. But I do have a suggestion for them. The next time they feel “instructive” I hope that they just write me a note on how to keep my equipment neat and tidy.

Support the Work

Contact: Keith Bildstein, Ph.D.

Sarkis Acopian Director of Conservation Science

570-943-3411 x108 or [email protected]

All Hawk Mountain research relies upon individuals and foundations to support this important work. If you or someone you know is interested in helping make a difference for birds of prey, please contact Keith for a confidential discussion.

Details from February Fieldwork

Caracaras in the Falklands

Keith just returned from a successful three-week research trip to the Falkland Islands where he has been studying the movement ecology of Striated Caracaras, or "Johnny Rooks," an island endemic raptor, and a globally near-threatened species with a population of no more than 2,500 birds.

During his February trip, he and colleagues trapped, color-banded, and collected blood for sex determination from 89 Striated Caracaras on two outer islands north of West Falkland Island: the 49-square-mile Saunder's and the 8-square-mile Carcass Islands.

On Saunders, 44 Johnnies were trapped bringing the total number of banded birds here to 247, or about 90 percent of all birds on the bigger island. Carcass Island is a new study site, and 44 birds were banded here, including six juveniles that had recently fledged from nests. In addition, at least 34 of the birds originally banded on Saunders were re-sighted on Carcass Island.

Hawk Mountain’s ongoing work with Caracaras represents the first long-term study involving color-marked individuals. Over time, these findings will help us understanding an individual bird's “ecological neighborhood,” which is critical to protecting the species. For example, it already appears that Carcass is a nursery island where the birds breed, and then travel to Saunders, and our re-sighting work is starting to make these movements more clear.

The next trip takes place in August, during the depth of southern winter at the study site, when caracaras are believed to be starving. On that visit we plan to do more banding and re-sight previously banded birds, as well as weigh all of the birds we capture to compare winter and summer body conditions.

At the moment, it appears the population of Striated Caracaras is stable, we intend to keep it that way. However the Falklands has been eyed for development of oil fields, and we hope to know enough by then about the charismatic Johnnies to make useful recommendations for their protection.