Raptorpedia

Raptors at Hawk Mountain

Each autumn, visitors flock to Hawk Mountain Sanctuary for the chance to see wild raptors sailing overhead as they pass on their annual migration to southern wintering grounds.

Learn more about the 16 species of raptors most commonly seen at Hawk Mountain.

Why do migrating raptors concentrate at Hawk Mountain?

Hawk Mountain straddles the Kittatinny Ridge or Blue Mountain, a 300-mile-long, prominent ridge that extends from 60 miles north of New York City to 20 miles west of Chambersburg, Pennsylvania. The Kittatinny is the southeastern most “corduroy hill” in the Appalachian Ridge-and-Valley Province of eastern Pennsylvania. Birds drifting south from Canada, New England and New York, slope soar the length of the ridge, saving energy on their journey south.

In the spring, prevailing easterly winds south of Hawk Mountain push raptors west of the Sanctuary, reducing spring migration to a small fraction of what it is in the fall.

Migration Strategies

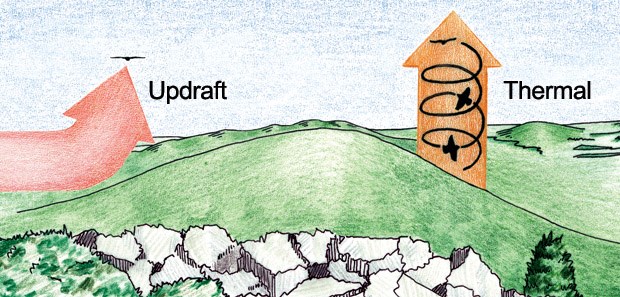

Relatively “broad-winged” species, including eagles, vultures and buteos, soar along updrafts and thermals to migrate long-distances. Such soaring migrants, which can cover 250 to 300 miles a day, tend to avoid crossing large bodies of water and follow longer, more indirect routes over land where updrafts and thermals occur. Many of these species fast for days while migrating.

Falcons, ospreys and harriers frequently use more active, flapping flight while migrating. Powered flight lets these birds take straighter, more direct routes across land and water. Many raptors, including accipiters that use soaring and flapping flight, often hunt daily in early morning or late afternoon while migrating.

Flocking

Raptors are solitary most of the year. Some species, however, flock while migrating. Ornithologists believe flocking enables hawks to locate and use thermals more efficiently. Broad-winged hawks start to flock in early September. Most broadwings pass Hawk Mountain within a six-day period in mid-September.

Timing

Hawks, eagles, falcons and other diurnal raptors migrate during the day. The raptors that rely mostly on soaring do not start their migration until strong thermals begin to form after 8 a.m.

In the northeastern United States, birds of prey migrate south from July through January. Decreasing day length in late summer induces zugunruhe, or migratory restlessness in raptors.

Weather strongly influences the timing of flights. In autumn, the passage of a cold front is often followed by large movements of raptors along the Appalachian ridges.

Seasonal timing also varies by species. At Hawk Mountain, the peak passage of broad-winged hawks, which depend largely on thermal soaring, occurs in mid-September. Osprey, bald eagles and kestrels are other early migrants. Large numbers of sharp-shinned hawks pass the Mountain in late September and early October. The peak of red-tailed hawk migration occurs in early November.

Soaring

Traveling long distances costs raptors a lot of energy. Before migrating, some hawks gain as much as 10 to 20 percent of their body weight in fat as a high-density fuel for migration. Raptors conserve precious energy on migration by soaring—using rising currents and columns of air currents to gain lift and fly without flapping their wings. Raptors “slope soar” by riding winds deflected up and over hills and mountains. Birds “thermal soar” by circling in pockets of rising, warm air called thermals. Thermals are created when the sun differentially heats the Earth’s surface. Hawks ascend quickly to thousands of feet within thermals, and then glide in the direction of their destination. Radar studies suggest that many raptors migrate at altitudes of 700 to 3,000 feet while soaring in thermals.

Hawk Mountain Geography

Aspen Cut.

A quarry of Martinsburg Shale 1.5 miles southeast of the North Lookout. Shale from Aspen Cut was used during the construction of the new Hawk Mountain Road in the 1950s. A campground is maintained here for sustaining members.

Donat.

A promontory at the western end of Shochary Ridge, eight miles southeast of the North Lookout in the Kempton Valley, midway between the Kittatinny Ridge and the Pinnacle.

Hemlock Heights.

A 1,519-foot Sanctuary ridgetop dominated by Eastern Hemlocks, 1.3 miles south of the North Lookout and west of Owl's Head.

Hunter’s Fields.

Several large, conspicuous fields in the valley floor, northeast of the North Lookout.

Kittatinny Ridge.

The endless mountain of the Lenape Indians. The ridge is a major “leading line” for southbound migrating raptors each autumn.

Little Schuylkill River.

A small river almost 1,000 feet down-slope, north of North Lookout.

New Ringgold.

A small town in Schuylkill County, 3.2 miles northeast of North Lookout.

North Lookout.

The official, 1,521-foot, count site at Hawk Mountain Sanctuary; one mile from the Visitor Center.

Numbers 1 through 5.

High points or knobs on the ridge read from right to left while looking east, 1.3 to 4.2 miles east of North Lookout.

Owl’s Head.

A 1,460-foot Sanctuary promontory, 1.8 miles southeast of North Lookout, and east of Hemlock Heights.

Pinnacle.

A 1,615-foot, thrust-fault promontory of the Kittatinny Ridge, 4.5 miles southeast of North Lookout. The Pinnacle offers one of the best views on the Appalachian Trail.

River of Rocks.

A 2/3-mile-long boulder field at the head of the Kempton Valley southeast of North Lookout. More than 30-feet deep in some places, it was formed 10,000 to 15,000 years ago when boulders slid from the ridgetops to the valley floor during the most recent Ice Age. Lowest elevation is 625 feet.

South Lookout.

A wheelchair accessible, 1,383-foot Sanctuary hawkwatch promontory, one quarter mile from the Sanctuary’s Visitor Center. South Lookout was established in 1967.