The Merlin is a small, dark falcon once known as the “Pigeon Hawk.”

Falco columbarius

67-year annual average: 44

1992-2001: 127

Record year: 176 (2001)

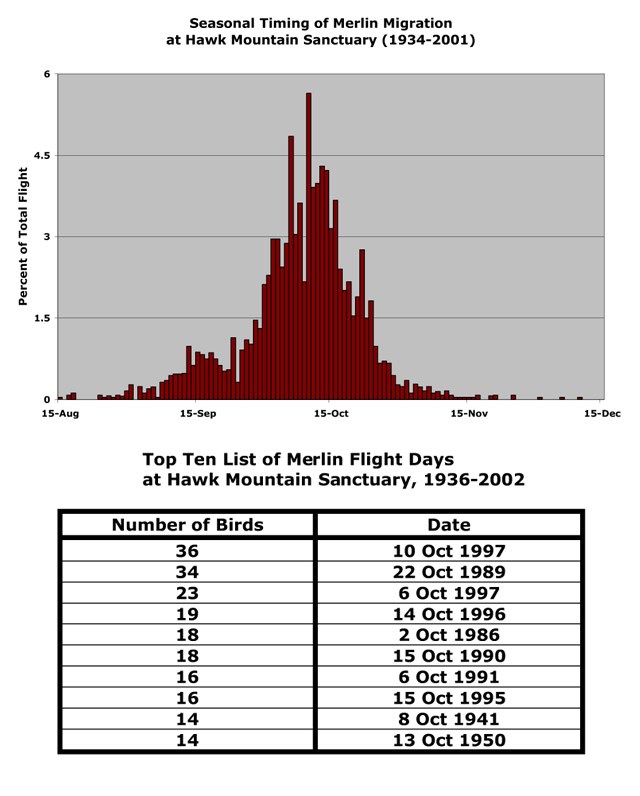

Best chance to see: Early October

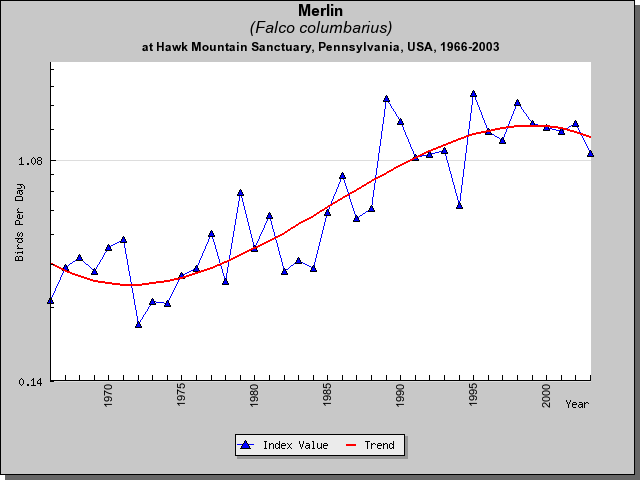

Longterm trends: Relatively stable through mid-1970s; increasing since the late 1970s.

A.K.A. Pigeon Hawk

Field marks: Dark, compact, pigeon-sized falcon, with pointed wings and a shortish tail. Heavily streaked below. Males have bluish backs; females and juveniles are brown

Flight behavior: Typically migrates alone. Occasionally soars, but typically flaps and glides while migrating. Strong, quick flight. Often dives on the Sanctuary’s owl decoy.

What Size is a Merlin?

- Wingspan2'-2'3"

- Length9"-12"

- W-L Ratio2.4:1

- 4.5-8 oz

Raptor Bites

- Merlins belong to the family Falconidae, a group of 60 species of caracaras, falconets, pygmy falcons, forest-falcons, and falcons.

- Were once known as pigeon hawks because their flight resembles that of pigeons (Columbiformes).

- In medieval falconry, Merlins were used by ladies. Both Catherine the Great of Russia and Mary Queen of Scots flew Merlins.

- Have slightly larger wingspans than American Kestrels, and weigh up to three times as much as kestrels.

- In North America, juvenile Merlins occasionally migrate in loose flocks, sometimes together with Sharp-shinned Hawks.

- Each Merlin eats as many as 900 birds a year.

- Few live to be five years or more, in part because they often collide with cars, buildings, and trees.

- Sometimes feed on birds such as pigeons, which are twice their size.

- Larger raptors sometimes prey on Merlins.

- The number living in urban areas has increased substantially in the last 30 years.

Seasonal Count – from North Lookout – 1934 to Date

Introduction

The Merlin is a small, dark falcon once known as the “Pigeon Hawk” because it somewhat resembles a pigeon in flight. Merlins are widespread, but uncommon throughout their range. In North America, Merlins breed in a variety of habitats in and around open areas in Alaska, Canada, and parts of northern and western United States. The species also breeds in Europe and Asia. Recently, Merlins have begun to occupy suburban and urban areas as well. There are 10 subspecies worldwide, thereof which (Taiga, Black, and Prairie) occur in North America. Taiga Merlins breed from Newfoundland west to Alaska and into the northern tier of the United States including the western mountain states, and are highly migratory. Most Black Merlin breed in the Pacific Northwest, and are sedentary. Prairie Merlins breed in south central Canada and in the northern Prairie states of the United States and are partial migrants.

Identification

Merlins are slightly larger than American Kestrels. Like other falcons, they have long, thin wings and long tails, and typically engage in active flight. The species is a direct and deliberate flyer that flaps with short, powerful, piston-like wingbeats. Unlike many other falcons, merlins lack distinct mustache markings on their face. Merlins exhibit six recognizably distinct plumages in North America. Adult males and females are distinguishable from each other, as are respective members of the three subspecies. Juveniles of both sexes resemble adult females. Prairie Merlins are lighter and Black Merlins are darker than Taiga Merlins. Adult males have bluish gray backs and wings, and black tails with two to five thin, gray bands. Their underparts have heavy, dark streaking with a rufous wash along the sides of the breast. Female Merlins have dark brown backs and wings, dark brown tails with thin, buff-colored bands, and buff-colored underparts that are heavily streaked. Females are about 10% larger in size and 30% heavier than males.

Breeding Habits

Merlins are typically monogamous. Members of breeding pairs winter separately, and each spring either a new pair bond is formed or an old bond is re-established. Merlins often return to the same breeding area, and many reoccupy the same nesting territory. Reuse of individual nest sites is less common. Males usually return to the breeding grounds about a month earlier than females. In some instances females remain on the nesting territory throughout the year. Merlins do not build their own nests, but rather use the abandoned nest of other birds, mainly those of other raptors or magpies. The species also nests on cliff ledges, the ground, buildings, and in cavities in trees. When nesting on cliffs or on the ground, Merlin create a depression or “scrape” in the substrate. Unlike other North American falcons that do not bring nesting material to the nest, Merlins sometimes add greenery or other nesting materials. Pairs begin to bond one to two months before egg-laying. Merlins engage in an array of aerial displays. Males use “power flying” (a display that involves flying with deep wing beats and rolling from side to side while traveling in strong, flapping flight)to attract females and to discourage intruding males. Less and more intense versions of “power flying” are performed by males and females as well. Both members of a pair also soar and “high circle” to mark their territory. In “flutter flight” displays, males fly slowly with quick, shallow wing beats in a circular or figure eight flight pattern near their perched mate. Courtship rituals also include food begging by the female, food transfers from the male to the female, and nest displays by both sexes. Merlins lay three to five eggs per clutch. If a clutch is destroyed early in the nesting season, a replacement clutch may be laid. Females do most of the incubating during the 30-day incubation period. After the eggs hatch, the female broods the nestlings continually for seven days. Once the young are at least a week old, females only brood them during inclement weather. Throughout this period, the male provides food for the female and the young. During incubation, males bring food back to the nest, and briefly incubate the eggs while the female feeds while perched nearby. After the eggs hatch, males call to females when returning to the nest area, and females then fly to the males to receive the prey for the nestlings. The young fledge when they are 25 to 35 days old. Two weeks after leaving the nest, fledglings begin to catch insects on their own, even so most young Merlins remain dependent on their parents for about five weeks after fledging.

Feeding Habits

Merlins hunt both from perches and on the wing. Like Accipiters, Merlins employ surprise when hunting from concealed perches and when flying rapidly below the canopy in attempts to flush prey. Individuals sometimes use hills and other landscape features to hide their approach. Although the species sometimes dives on prey, Merlins do not typically execute high speed stoops from great heights. Hunting activity peaks in early morning and late afternoon. Merlins frequently cache surplus food both in winter and in the breeding season. Males cache surplus food near the nest, and females retrieve such items when the male is late in returning with food. Merlins feed primarily on birds. Although the species takes birds as large as pigeons and small ducks, it usually feeds on small- to medium-sized songbirds. In urban areas, House Sparrows are a major component of the diets of many Merlins. Merlins often prey on small shorebirds, particularly in winter. The species also feeds on small mammals, reptiles, amphibians, and on insects. Overall, Merlins are opportunistic hunters that feed upon the most abundant and vulnerable prey available.

Migration

The Merlin is one of 26 North American raptor species that are partial migrants. Like other falcons, Merlins often use flapping flight while migrating. The species also soars on mountain updrafts and on thermals, but apparently does not require them to complete its migratory journey. Merlins, which regularly undertake long water crossings, fly in light rains as well as early and late in the day. In autumn, females precede males on migration. In spring, males precede females. The migration patterns of the three North American subspecies differ considerably. Taiga Merlins are complete migrants. Each autumn, almost all members of this subspecies leave their breeding grounds and migrate to their wintering grounds in the western and southeastern United States, and the West Indies, Mexico, Central and northern South America. Black Merlins are typically sedentary. Only individuals breeding at the northernmost part of the subspecies range travel south, and these individuals generally overwinter within southern parts of the subspecies breeding range. Prairie Merlins are partial migrants. Many migrate to the southern United States and in Central America, but others, particularly individuals breeding in urban areas, where songbird prey are common in winter, remain on their breeding grounds. Hawk Mountain’s long-term (1934-2002) average count for merlins is 46. The average count for the past ten years (1993-2002) is 134. The peak of the Merlin flight at the Sanctuary occurs in early October.

Conservation Status

The current world population of Merlins is between one-hundred thousand and one million birds. In the 1800s Merlins declined in parts of their range as a result of persecution. The species suffered more serious declines in the 1950s, 1960s, and 1970s due to the widespread use of organ chlorine pesticides including DDT. When Merlins consume prey containing pesticides such as DDT, these chemicals accumulate in a Merlin’s fatty tissues and subsequently reduce reproductive success through eggshell thinning. Following bans on the widespread use of DDT in 1972, Merlin numbers began to increase in the 1970s and have continued to do so since. The species has experienced declines in some areas due to habitat loss and human disturbance. The species now breeds both in urban areas in the northern United States and in southern Canada. Urban areas are favorable breeding locations because they afford safe nest sites and abundant songbird prey.

| BWHA Trends | ||

| Year Range | Trend Value | P |

| 1970-1980 | 3.4 | 0.01 |

| 1974-2004 | 5.1 | <0.0001 |

| 1980-1990 | 8.2 | <0.0001 |

Merlin Reading List

DUNNE, P., D. SIBLEY, AND C. SUTTON. 1988. Hawks in flight. Houghton Mifflin Company, Boston, Massachusetts.

FERGUSON-LEES, J. AND D.A. CHRISTIE. 2001. Raptors of the World. Houghton Mifflin Company, Boston, Massachusetts.

JOHNSGARD, P.A. 1990. Hawks, eagles, and falcons of North America. Smithsonian Institution Press, Washington, D.C.

SODHI, N.S., L.W. OLIPHANT, P.C. JAMES, AND I.G. WARKENTIN. 1993. Merlin (Falco columbarius). No. 44 in The Birds of North America (A. Poole and F. Gill, Eds). The Birds of North America, Inc., Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, and The American Ornithologists’ Union, Washington, D.C.

WEIDENSAUL, S. 1989. North American birds of prey. Gallery Books, New York, New York.

WHEELER, B.K. 2003. Raptors of eastern North America. Princeton University Press, Princeton, New Jersey.

WHEELER, B.K. AND CLARK, W.S. 1999. A photographic guide to North American raptors. Academic Press, San Diego, California

Bent, A.C. 1937-1938. Life histories of North American birds of prey. (vol.1-2). New

York: Dover.

Brown, L., & Amadon, D. 1968. Eagles, hawks and falcons of the world. New York:

McGraw-Hill.

Cade, T. 1982. Falcons of the world. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

Dunne, P. 1995. The wind masters. Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

Johnsgard, P. 1990. Hawks, eagles and falcons of North America. Washington DC:

Smithsonian Institute Press.

Orton, D.A. 1980. The merlins of the welsh marches. London: David & Charles.

Sodhi, N.S., Oliphant, L.W., James, P.C., & Warkentin, I.G. 1993. Merlin

(Falco columbarius). In The Birds of North America, No. 44 (A. Poole and F. Gill, eds.).

Philadelphia: The Academy of Natural Sciences; Washington DC: The American

Ornithologists’ Union.

Field Identification

Clark, W.S., & Wheeler, B.K. 1987. A field guide to hawks of North America.

Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

Clark, W.S. & Wheeler, B.K. 1995. A photographic guide to North American

raptors. San Diego: Academic Press.

Dunne, P., Sibley, D., & Sutton, C. 1988. Hawks in flight. Boston: Houghton Mifflin.